The Hidden Civil War Artifact at Central Prison

There’s a hidden treasure in Raleigh, but unfortunately it’s not publicly accessible because it’s on the grounds of Central Prison. Of all the relics of Raleigh’s involvement in the Civil War, this is one of the most important as well as one of the most hidden. It’s an inscription on a rock made by a Union soldier made during the northern army’s occupation of the area.

A Look at Raleigh’s Entrance in to ‘The War Between the States’

Many locals don’t realize it, but Raleigh has a rich history in the Civil War beyond having the two cemeteries (Raleigh National and Oakwood) of the time period.

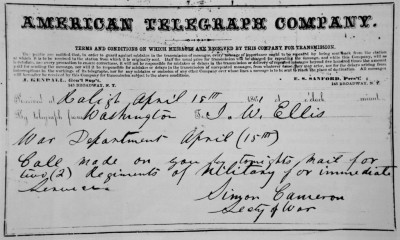

This telegraph from the US War Dept. pushed NC to secede from the Union. Lincoln's Sec. of War ordered Governor Ellis to supply troops to assist in putting down the rebellion at Fort Sumter.

In the months leading up to the outbreak of war, North Carolinians were evenly split on the issue of secession. That changed abruptly after the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina. On May 20th, 1861, The North Carolina Legislature had a convention on secession in Raleigh. Unanimously, all delegates voted in favor to the sound of bells ringing and 100 guns firing. Union Square was then renamed to Capitol Square.

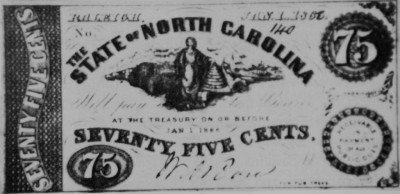

Raleigh was where the state’s new currency was printed and home to the state’s first military hospital. Before the delegation had even voted to secede, local citizens formed Company A of the 10th North Carolina Regiment at the first location of the State Fairgrounds. Churches sent their bells to melted down for scrap metal, and a munitions plant sprung in to operations in the NC School for the Blind and Deaf.

Raleigh was considered to be incredibly safe during the war. Jefferson Davis, the Confederate President, had his wife and children stay at St. Mary’s School for a while during the war. It was also where Confederate general Robert E. Lee sent his daughter.

Raleigh’s Surrender and ‘The Last Hurrah’

In 1865, Zebulon Vance of Buncombe County was the governor of North Carolina, and according to legend it is he who haunts the Capitol Building. Once news arrived that General Sherman had occupied Fayetteville and was advancing, he fled to Hillsborough. Former NC governor Swain approached Sherman about a preliminary truce. Days later, Raleigh mayor Harrison and other citizens crossed Walnut Creek to meet Union General Kilpatrick to negotiate an official surrender. Many locals had heard of Sherman burning the vast majority of city buildings during the Battle of Atlanta, and were eager to avoid the same fate.

As General Kilpatrick’s cavalry was marching down Fayetteville Street after the city’s surrender, a lone member of  the Confederate Army fired a shot at advancing forces, shouting “Hurrah for the Southern Confederacy!”. He became the subject of a pursuit, then was hanged by Union forces in Burke Square (now home to the Governor’s Mansion). There is a local mystery involving Lt. Walsh as every year in April someone decorates his grave in Oakwood Cemetery.

An Occupied Raleigh, and the Source of the Artifact

Several parts of Raleigh were occupied by Union troops after the city’s surrender. The previous location of the Governor’s Mansion (now destroyed) was home to General Sherman and the Haywood House on Blount Street (above) was the headquarters for Gen. Francis Blair. Sherman was in Raleigh upon receiving news of Lincoln’s assassination, and it took all he and his generals could muster to prevent troops from seeking revenge on local citizens and infrastructure.

Perhaps the largest contingent of Union troops was located on Dix Hill, where the Union soldier that etched his name in stone was stationed. Part of this area is now known as Central Prison.

Uncovering History

Late last week I had a reader contact me to inquire about a ‘large marked stone’ inscribed by a Union soldier within the grounds of North Carolina Central Prison (thanks Hal). He noted that he had not visited the site in more than 10 years, and was worried that it could have been lost during recent changes to the landscape.

I decided to spend my weekend pretending to be an archeologist (what I wanted to be when I grew up) and look for the stone. Central Prison isn’t really accessible, and finding this did take a bit of exploring after initially being denied entry by an on duty guard.

Once I was sure I found the proper stone, I spent more than 30 minutes clearing away moss and debris from the rock. At first I traced with a twig, and then later my fingers, over the grooves carved into a rock nearly 150 years ago. Lines came together, and the first word I put together was the soldier’s last name: Dixon. Other parts of the inscription were:

Wilson Dixon

Company C 1st Mo.

Engrs.

According to the National Park Service, Wilson Dixon’s rank was Artificer, a skilled craftsman usually attached to an engineering group. An interesting part of the inscription is the backwards S’s. Engineers aren’t typically known for being great at linguistics, so this doesn’t come as much of a surprise.

Left to Wilt

There is no historical marker, and it isn’t easy to see this piece of Raleigh Civil War history. It’s on North Carolina state property, and prison officials are likely not eager to have tourists traipsing about. On both of my visits to the rock, I was reminded by a guard that “this is a maximum security prison”, and as such, was ejected from the premises.

There are other interesting things to find on the rock. One example is this lone 'W', which may have been practice for the (presumably) young Union soldier.

It’s a shame that such a priceless part of Raleigh’s history is hidden. In the past, the City of Raleigh has been able to get property easements from the state and private landowners for projects such as the Greenway. They should be able to do the same here as it isn’t located in the middle of the complex. It sure would be nice if the city could claim this for its cultural heritage, restore and preserve it, and allow interested citizens to see it.

In recent years reminders of the Civil War have been brushed under the rug under the pretense of tolerance, and it’s a real shame. Whether or not you agree with what our forefathers fought for (or against), pretending history didn’t exist is erasing their experiences. It’s erasing what so many fought and died for. You know how that saying goes about those that forget history.

This artifact of the Civil War is priceless and deserves nothing less than to be memorialized and protected.

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

02/07/2011

John, everything you do is so interesting.

02/07/2011

Great post on Raleigh’s hidden Civil War history. A couple friends and I tried to find it years ago and were also run off by the prison guards. It was only recently that I went back on my own and –eureka!– I found it! There is a secret way to get to it that puts you out of the line of sight of the guards.

02/07/2011

Hi John – Great post. I’m glad this piece of hidden history is finally seeing the light of day!

02/07/2011

very, very interesting. I would wager that your discovery and research efforts and the recording of such go a long way toward preserving this in absence of official government action. Things like this, in that they are not readily known, nor easily accessible, usually make the artifact that much more coveted by those that become aware of it. IMO, much cooler than a dug up rock artificially placed on a pedestal in some centrally located area of town or in a museum.

02/07/2011

LB – I didn’t make this entirely clear, but I think removing this stone to put somewhere else would be a travesty. My ultimate goal for this artifact would be a restoration (gently clearing away debris and moss), some sort of plexiglass cover for it, and a historical marker — but in its original location.

Not including the bureaucratic red tape involved in any interaction with a state or city agency, I honestly do not think it would take much to achieve this. Despite being on prison grounds, it would be easy to facilitate pedestrian access while retaining security for the prison.

If anyone has ideas on ways that we could persuade either the City of Raleigh or State of North Carolina to make a move and protect this, please leave a comment here or contact us.

02/17/2011

Just as a thought. Why not see if the stone could be moved- slightly to across Western Blvd from the prison to Dix proper? That would take it away from the prison that they don’t need and put it near the soccer fields that people use all the time. Would give people something else to do while visiting the fields and save a piece of history that is tucked away and unacessable.

03/06/2011

It’s funny that you say you had a hard time getting to the rock. I have a friend who lives in the Boylan Heights area and as 10-year-old kids we would walk right up to that rock and play around it. We never got in trouble with any guards but this was 6 years ago so…I guess things have changed. Thanks for this awesome article!

03/20/2013

there is another rock the same size across the street on dix property that also has many civil war era inscriptions on it…they are difficult to read though….it is on the right just before the soccer fields….

03/20/2013

Phil: If you have any photos of this second ‘Yankee Rock’ send them to us and we’ll post them here in an update.

09/24/2013

re: the other rock on Dix property. I examined it this weekend and I could read the name “Thomas” and that’s about it. There are one or two backward S’s. and what looks to be Roman numerals followed by what looks like “Mi” as to maybe indicate Michigan The chiseling is shallow and the rock covered with dark lichens.

10/14/2013

Does anyone have a tip or two on how to find the rock I would love to see this piece of history

10/15/2013

Walsh wasn’t hung in Burke Square…if you read Elizabeth Reid Murrays account he was hung NE of Burke Square in someones “grove”…I forgot the exact name of the grove.

04/09/2021

A local who’s aunt lived on Lane St. east of Bloodworth said it was along that block. She used to point the house out to him. To his recollection, it was closer to East St. than Bloodworth. She was told by those who were alive at the time, so that is definitely not Burke Park. It was an oak wooded grove back then, as told by the town historian in 1876 (Mr. Battle). The troops were supposed to hang him away from the “sight of women and children”, so Burke Park seems to me too public a square and would not be following orders.

04/09/2021

Found corroborating evidence. Eye witness account published in the N&O on 15 April 1928 where C. B. Edwards tells of the Lt. Walsh story and that he was “executed upon an oak tree in a grove where now is the corner of East Lane and East street.” Link to article in newspapers.com which you might get a free look or else need a subscription. I kept a clipping.

04/09/2021

Link: https://www.newspapers.com/image/651047255/?terms=Lt.%20Walsh&match=1