A Storied Structure: The Heck Andrews House — Inside Out

Over the years, some have gained illegal entry and many have fogged the first floor windows with curious eyes, but the good stuff is deeper, structurally and intellectually. This past summer, Goodnight Raleigh staff were given access to the entire house — from basement to widow’s walk — for the purpose of documenting the interior.

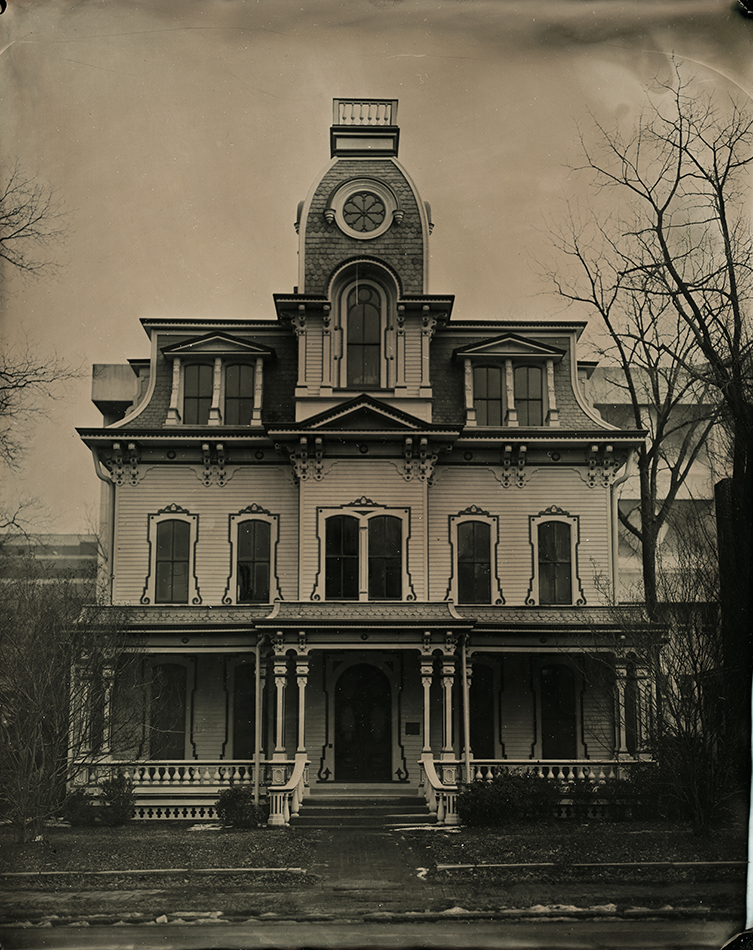

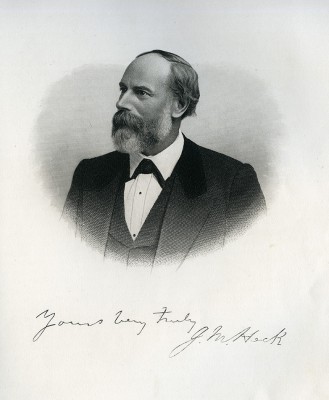

Houses, as with many things we make or build to suit, tend to reflect the predilections and characteristics of the creator. The Heck-Andrews house certainly fits the man who commissioned it.

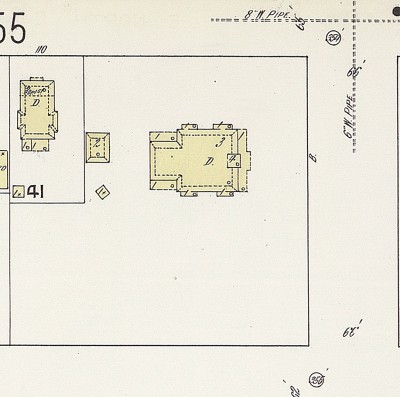

The lot Mattie Heck purchased ran the length of the block along Blount Street. An attractive location at the end of a main residential street, just far away (and just close enough) to town.

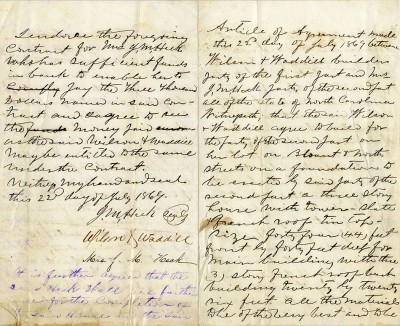

A little more than two months later, a contract was drafted to build the house.

An excerpt from the contract between builders Wilson & Waddell and Heck reads:

[A] three story house with tower slate and french roof, and tin top size forty four (44) feet front by forty (40) feet deep for main building with three story french roof. Back building 20—26 feet. All the materials to be of the very best and to be put up in the very best manner according to the plans and specifications of the superintendent architect G. S. H. Appleget.

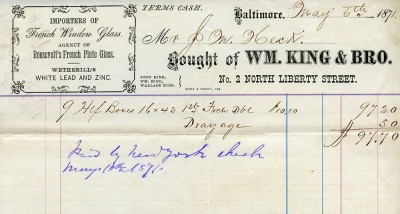

Mattie Heck was probably tasked with handling business transactions and aesthetic decisions during the construction of their new house. She insisted on high-quality French window glass. An excerpt from the contract reads,

“Said Wilson and Waddell to furnish all the materials for the work to be done by them, but it is agreed that shall the party of the second part [Heck] conclude to have glass better than first class American, which to be furnished by the said, Wilson and Waddell, then in that case the said party of the second part shall pay the difference in the price of the said American glass and the said better glass as far as she orders the change of glass she made.”

The contract reads like 19th century stereo instructions, but basically, the builders weren’t going to foot the bill for her fancy foreign glass. Below is the receipt for said glass, imported from France to Baltimore, Maryland–one of America’s largest ports at the time.

Heck’s optimism and confidence in the post Civil War new age is clearly displayed in the elegant, yet bombastically, styled house. It sits with conviction, possessing an air of readiness–as if it could break free of its moorings and sail away at will.

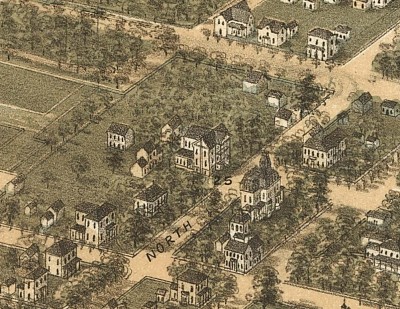

In 1869, Blount Street terminated at North Street, and just as you’d expect to see in a planned city, Raleigh’s boundaries were North, South, East and West Streets. Col. Heck built his house on the edge of town. Big things were afoot for Raleigh at that time. Heck’s house was an important rudder for development along North Blount Street, as well as the former Mordecai Grove, which would later become Oakwood.

In the years following the mansion’s completion, as the last quarter of the 19th century faded, Heck played a major role in the burgeoning residential development in the northeast quadrant of Raleigh.

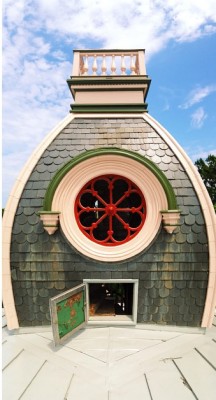

The Heck-Andrews house is a wonderful example of Second Empire style. The four-story tower, extensive ornamental woodwork, concave mansard roof and repetitive detail are all executed with a fine sense of proportion and aesthetic. This style of architecture became popular around the mid-1860s during the Second French Empire as it was being extensively used in Europe for commercial, municipal and residential buildings.

A steep mansard roof with dormer windows and tower are the style’s most identifiable characteristics. To an American, especially a southern American, this distinctly European style was likely seen as stylish and modern in contrast to more traditional styles of the day that either gave a nod to the past or emphasized function over ornamentation and pretense.

Heck Family Era

The Heck family, Jonathan, Mattie C. and their children, Loula, Fannie, Minnie, George, and 3-month- old Mattie Anne moved into the giant house in 1872 all eyes on the future.

Heck family members with servants — Mattie Heck sits in window. Taken on the south lawn c. 1890. The fountain in this photograph is currently at Peace College. Photograph courtesy of Charles Heck, great grandson of Col. Jonathan Heck.

The next 30 years bore business venture successes and failures, nine children, birthdays, marriages, and deaths. By 1910 only Heck’s widow, Mattie, the family matriarch, and two of her children, Fannie and Pearl (with the help of two servants) resided in the house. A generation began and ended under one mansard roof.

In 1916 Mattie Anne Heck Boushall and her husband Joseph moved into the mansion. Subsequently, matriarch Mattie Callendine Heck moved out of the house where she’d raised her family. After which the mansion was sold to Alexander Boyd Andrews Jr., son of railroad baron Alexander Boyd Andrews. For the first time in half a century, there were no Hecks on the corner of Blount and North.

A. B. Andrews, Jr. Era

Shortly after taking ownership of the house in 1921, A. B. Andrews, Jr. performed an extensive renovation which included updated plumbing and electrical systems, interior aesthetics and general repairs. Sadly, Andrews’ wife Helen, age 43, died of a stroke before she could enjoy the house her husband had lovingly purchased for her. Andrews occupied the house for just shy of 30 years, taking full advantage of the home’s ability to impress. He frequently entertained, but never married again.

Julia Russell/Gladys Perry Era

In 1948 the house was purchased from the Andrews heirs by Mrs. Julia Russell. Mrs. Russell likely got the creaky old mansion for a song. Her daughter, Gladys, a stenographer for the DMV, moved in with her mother.

When Mrs. Russell bought the house it had been nearly three decades since it had seen any updates. The interior likely appeared only slightly better than it does today and Mrs. Russell didn’t change a thing. This detail is especially interesting. It is rare to find a house that hasn’t been updated since the 1920s, and because Mrs. Russell didn’t alter the house structurally or aesthetically, the interior is a time capsule of residential design. There are gas light fixtures still installed, and a long-abandoned load of coal in the basement. Nothing has been modernized, sanded down or painted over. The house is dirty, dusty, and rotten in parts, but it is all there.

After Mrs. Russell’s death sometime in the 1970s, Gladys had the place to herself. In the later years of her life she was known to wander the streets of Raleigh, rifling through trash barrels and dumpsters for items that happened to catch her eye. It is said she preferred to cover her face in thick, white “pancake” makeup in an effort to appear as a ghost — thinking people would most certainly steer clear. Her bright red lipstick, black dress and overcoat completed the guise.

You can read more about Julia Russell and Gladys Perry in Reminiscences of a Raleigh Boy, Part 7: The Ghost of Blount Street

So, what exactly is inside?

Nothing, really.

The house is, however, one of the most intriguing and beautiful empty houses your narrator has ever seen.

The house is three stories, with a four-story tower and full basement. As you walk in the front entrance you are greeted by a large staircase. Immediately to the right is the reception room, and to the left, the library. The reception room opened onto the family parlor, and the library led into the dining room, the kitchen was located in the rear wing. Originally, each of the first-floor rooms (four in total) featured large bay windows opposite a stately fireplace.

Detail of ground floor fireplace surround.

In 1921 during A. B. Andrews extensive renovation, the two front rooms lost their fireplaces–chimney and all. These two rooms and the central hallway were opened up to create a space spanning the width of the house.

House seen from south lawn c. 1895. Photograph courtesy Charles Heck, great grandson of Col. Johnathan Heck.

Above, the two chimneys that were removed can be seen closest to front of house.

What follows is a pictorial tour through the Heck-Andrews House.

Ground Floor

Left front reception room note the large radiator. Innovations in residential heating soared in the 1920s. Central heating was a large part of A. B. Andrews’ 1921 renovation. These large radiators are found on all three floors and supplied by a large furnace in the basement.

View from the central hallway looking toward the front door. The Neoclassical interior details like the Corinthian columns seen here, were also part of Andrews’ 1921 renovation.

View of columns looking across central hallway into the library.

An elegant gas chandelier hung beneath the plaster medallion seen here in the dining room.

Ground floor looking toward front door. The basement entrance can be seen on extreme right, stylistically obscured by the woodwork along the side of the staircase.

Pictured above is the family parlor. The door seen on right leads outside to a porch on the right side of the house.

Side entrance. This portion of the house was heavily damaged by leaking rainwater. Stabilization efforts in 1999 have stopped any further deterioration.

Grand hall staircase leading to second floor.

Second Floor

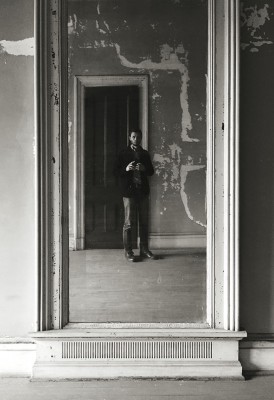

Second floor central hallway.

As you approach the second floor, a large central hallway opens, displaying an array of doorways and windows. A glance into the floor-to-ceiling mirror seen on the right resets your sense of scale. — A friendly reminder from a long-dead interior designer: “You are a small being in a very large house — thank you for your attention.”

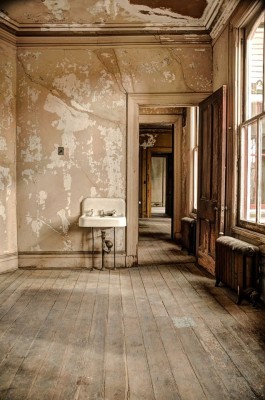

The two images seen above depict one of the four second-floor bedrooms. Sinks are found in all the bedrooms in the house, and while that may seem odd at first, it actually makes sense. Before advances in indoor plumbing most people were accustomed to having a washstand in their bedroom for the occasional face wash or garment rinse.

Typically, in the 19th century, well water was carried inside and decanted into large pitchers that would sit on the washstands next to a basin. Plumbed sinks found in bedrooms can be seen as a natural evolution from the days of wooden washstands. In the early days of indoor plumbing, having a sink in your bedroom with all the water you needed on demand was considered a quite a comfort.

The master bedroom on the second floor is depicted above. It is the only bedroom in the house that leads directly into a bathroom. It is very likely that this is the room in which the final resident of the house, Gladys Perry, spent her final years–in isolation, surrounded by her treasured detritus.

Second floor bathroom.

Detail of a 1920s cast iron toilet basin on second floor. Part of A.B. Andrews 1921 renovation. If there ever was a beautiful toilet, this is it.

Third Floor

After a walk up some decidedly rickety stairs that lead to the third floor, the mansard roof makes an appearance. The interior walls in the rear wing are pitched with the windows set out to sit vertically–a construction detail that your narrator found very intriguing.

Above, a curved hallway on the third floor, rear wing. A small bathroom is located just through the doorway. Around the bend is another large central hallway with floor-to-ceiling shelving.

At the end of the third floor central hallway are french doors with a large glassy surround. Just beyond is the spiral staircase that leads to the tower–and ultimately, the widow’s walk.

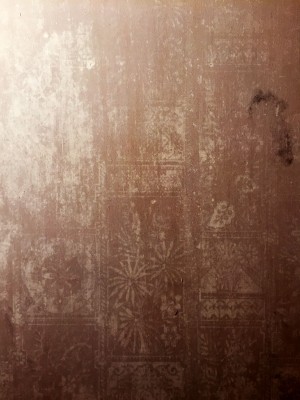

Third floor bedroom. The walls in this room have a wonderful texture only time and neglect could create. Upon closer inspection the pattern from wallpaper, likely hung more than century ago, has left its mark on the bare plaster.

Seen above is one of the four third-floor washstands. The sinks on the third floor have a single cold water spigot flowing into a porcelain basin with a hand carved marble counter and back-splash. They are really quite beautiful–and very early examples of indoor plumbing. They are, in effect, automatically filling wooden washstands.

Little is known about how the original plumbing was configured, but it is certain that the house started life with some arrangement of water pipes, however primitive. A mention of a sink, bathtub and “pipes to carry water and the lead-ing of water tank” is seen in the written plans for the house. Indoor plumbing was exceedingly rare in 1869 and it is probable that the house started out with one central sink connected to a cistern or tank, likely located on the third floor. The Heck family servants would then tote buckets of water filled from this central sink to various locations around the house.

If one sink sounds paltry for such a large house, keep in mind that the Heck-Andrews House was built nearly two decades before Raleigh had a municipal water system. It is feasible that the sinks such as the one pictured below, were not installed until after the house was connected to Raleigh’s municipal water system–sometime around the early 1890s.

View looking toward back of house from front, third floor bedroom. Sinks in both bedrooms can be seen.

Two bedroom doors meet.

Above, the spiral staircase leading to the tower. At the center of the frame is the nearly vertical stairway leading to the hatch for the widow’s walk.

Raleigh’s 19th century answer to an observatory, the tower windows offer a wide-reaching view of the surrounding neighborhood. The City of Raleigh as seen from the tower in the late 1800s would have looked considerably less crowded than today.

Looking down on Blount Street from tower. The Hawkins-Hartness House (c. 1882) in full view.

The two remaining chimneys. View looking toward rear of house from roof access hatch in tower.

Rear of tower as seen from roof. Access hatch can be seen open at bottom. The widow’s walk is the small area at the very top of the tower surrounded by a low balustrade. It has been told that the wives of seamen would watch for the return of their spouses ships from this vantage point on coastal houses. All too often, the sailors were claimed by the sea, leading to the term “widow’s walk.”

Present and Future

The State of North Carolina put the house on the market in late 2015, less than a year after the exterior of the house was completely repainted. As of January 2016, the 144-year-old gal sits patiently waiting for a new owner.

If it’s true what they say about things that matter being on the inside, then much like Gladys Perry, the mansion is but a ghost of its former self. With fresh red lipstick and pancake makeup the old place excites feelings of suspicion and intrigue.

Houses such as the Heck-Andrews House were built during a time when the distance between a craftsman’s hands and the final product was little more than the length of a hand-tool. Every roof slate, every linear foot of baseboard, floorboard, molding, every piece of plate glass, every strip of wood lath and every decorative detail had a person’s hands behind it. The mansion is just as much a residence as it is a piece of 19th century sculpture.

For a mere $950,000 this house could be yours. What the real estate listing doesn’t mention is the enormous amount of historical knowledge, money and love required to bring this structure back to life.

…Mainly love.

“What makes a house grand

ain’t the roof or the doors

if there’s love in a house

it’s a palace for sure

without love

it ain’t nothin but a house

a house where nobody lives.

Without love it ain’t nothin but a house,

a house where nobody lives.” -Tom Waits

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

12/31/2015

Beautiful. Inside and out!

12/31/2015

Beautiful.

12/31/2015

Mr. Dunn, you have produced a masterpiece worthy of your subject! Wonderful old photographs, gorgeous new photographs, excellent research, insightful analysis, and beautiful writing. Thank you for this gift!!

12/31/2015

Wonderful article; brings back memories of seeing Ms. Perry walk the local streets in that ghostly white makeup.

Thank you.

12/31/2015

This is absolutely amazing. Thank you for taking these pictures and posting!

12/31/2015

Before the Hawkins-Hartness House became the Lt Gov’s office, it was the offices of a small division of the Stage Planning Commission that did planning & design for small towns & areas without their own planners/architects. My mother was the librarian, with the library housed in the small brick building behind the home (likely at one time the kitchen and storage). I loved that library, and as a late 60s teen devoured the incredible & expensive book & magazine collection. In some aspects it exceeded the resources of the NCSU School of Design Library (tho its full collection of the greatest design periodical ever – the British monthly Architectural Design was priceless)

01/01/2016

Thanks for the images and terrific documentation!

01/01/2016

Way to go Ian, what a wonderful article. I am guilty of peering into these windows almost every time I walk by and wishing I had infinite funds to buy and enjoy this home.

01/01/2016

My wife and I were among the many volunteers who helped sweep the place out decades ago. Then we simply knew it as an old house, and I can recall little about that day (beyond sticking my head out of the rotten trap door in the tower) or what the interior looked like. This is a terrific reminder of all that and of an important slice of Raleigh history — thank you for the detail! (Is there info on the then-empty lot next door? Maps suggest a garden with a circular drive in the middle, part of what may have seemed more an “estate” than merely a big house.)

01/01/2016

I love this old house, thanks for the pictures and history…

01/01/2016

This is a wonderful! This beautiful house captured my imagination as a small child passing by and I have always wanted to explore the inside. Your photographs and descriptions are fascinating. Thanks!

01/01/2016

Ian,

Thank you for writing such a wonderful article about the house and its history. I enjoyed reading about my Great Great Grandfather, Great Great Grandmother and others who lived there.

Also…Great pictures.

Thanks to the archives as well for giving my family a last look/tour of the house. It was memorable and very informative.

I’m hoping whoever buys the house will turn it into an event hall, an upscale restaurant, or some other public venue my family can visit in the future.

01/01/2016

Thanks for the tour, without opening a door, viewing the historic decor, with exquisite photos galore. A jewel of a Tar Heel treasure deserving of a loving family to make a house into a home again.

01/02/2016

This is amazing, Ian! Thank you for sharing the history and beautiful photos. Very well done!

01/02/2016

Beautiful photos and narration…an awesome tour! I now want to hear the family stories. Thanks for sharing.

01/02/2016

If we all could live as simply and work as hard as they did. We are a much different era.

01/02/2016

great writeup and photos

01/02/2016

I love this home and have been interested in it for about 25 years! Thank you so much for writing this article on a house I have loved for so long

01/04/2016

I have very fond memories of this house and of Ms Perry from the mid 1980’s. I had come to live in Raleigh for a few years from London and worked as a volunteer for Operation Raleigh, whose headquarters were on the top floor of the State Visitor Center located in the historic house next door.

We were totally fascinated by Ms Perry. During the summer months, we often used to sit outside on the fire escape balcony which afforded a bird’s eye view of the Perry house and of the curious comings and goings of its occupant.

We English are no strangers to eccentricity (!) and for me, Ms Perry could have stepped straight from the pages of Dickens. She was magnificent. Occasionally she would look up from her Herculean task of sorting, sifting and curating all the many decades’ worth of Raleigh trash which she squirreled away in her home, and cast a baleful eye in our direction. The thick, white pancake make-up for which she was renowned had coalesced, in her later years, into a thick, plaster-like mask, particularly over her nose. We did wonder if this was in part to offer some protection from the abominable odours sometimes emanating from her house. We could see through her windows to the mountains of trash piled up inside and witnessed her returning from her collection forays with new treasures.

Although she was certainly immersed in a strange twilight world of her own, we nevertheless had no sense that she was unhappy. On the contrary, she seemed gloriously cantankerous and strangely content.

It has been such a treat to take this wonderful pictorial tour of

the house ( for me, it will always be the Perry House). It reminds me of a particularly happy period in my life and of the dear and special friends who shared that balcony with me. I am due to visit Raleigh later this month and I hope to be able to take a closer look.

01/04/2016

Thank you for that, Julia.

01/05/2016

Thank you for a great article about a wonderful, historic house and families. The Heck’s daughter, Fannie, was a very important woman in the history of Raleigh and Baptists. Her legacy was celebrated by Woman’s Missionary Union of NC this past August, with Gov. McCrory declaring Aug. 25, 2015, Fannie Heck Day.

It was fun to see the house through you eyes.

01/05/2016

Are the locks on the outside of the bedroom doors?

01/13/2016

Thank you so much for the wonderful pictures and beautiful story of this gorgeous house! I am in absolute love with the house and wish I had the money to purchase it and make it whole again. But…..

I have spent a lot of time trying to find inside pictures and information on the house. This, by far, is the MOST and BEST of pictures and info.!!!

Thank you, thank you, thank you!

01/28/2016

I LOVE old houses and their histories. Since moving here in the late 80s, I’ve longed to get a look inside this particular house. Now you’ve given me a glimpse. Thanks so much.

01/30/2016

Thank you Ian for this fascinating glimpse inside a house that has held me spellbound since the first time I saw it at the age of 10 in 1990. I always wondered what lay within those walls, and it’s a treat to finally see. Wonderful photography, beautifully written, and a first-rate record of its current time capsule state. Hopefully the new owners will give it the care it deserves to last another 150 years!

01/31/2016

I moved to Raleigh in 1977 and worked downtown, often seeing Ms. Perry heading down Salisbury St. past my office windows. She usually wore a dark wig and always the white mask-like makeup on her face. She walked in the roadway, not on the sidewalks, and refused to move to a place safe from the passing traffic. She would rummage through the trash cans – I never saw her speak to anyone.

I have followed the history of the Heck-Andrews house for years – your previous article being of great interest and help. Now you have at last managed to show us the interior. . . . . . . and it’s wonderful gift you are sharing with us here in this post. The photos are fabulous. Thank you so much.

I walked by the house yesterday and took some photos for an update of the property on my blog. It looked beautiful in the Saturday sunshine and, from what I read in the N&O this past week, has now been purchased by the N.C. Assoc. of Realtors for $l.5M. Will they renovate or sell it on? Who knows, but apparently whoever eventually comes up with the money will need, as you say, a lot of love too. This beautiful house deserves the best, they don’t building them like that anymore!

02/02/2016

Looks like it has a prospective buyer; for over the asking price.

http://www.bizjournals.com/triangle/blog/real-estate/2016/01/historic-heck-andrews-north-carolina-realtors.html

02/13/2016

A beautiful narrative of a lonely house.

02/21/2016

Excellent article, history, and presentation. Been awhile since I’ve visited this site, but always gratified at what I find that I have been missing.

Great work to all, and keep it up!

06/15/2016

Wish life had given me a million dollars with which to do good deeds. I’d renovate that jewel in a heartbeat. Thanks for the ultimate chronicle. Beautiful, and important.

07/17/2016

Thank you Ian.

01/14/2017

I believe a friend of mine told me months ago that he is designing the renovation.

Lucky bugger!!!

03/20/2017

Like many folks, I have always been fascinated by this house. Easily the most ornate of all Raleigh Dwellings. Back in the early 90’s myself and a friend (after a night of drinking) crawled through the cast iron coal chute door into the basement coal bunker and treated ourselves to a midnight tour. I don’t remember much of the details -I think that one of the ground floor rooms had a huge room length plate glass mirror on one wall. I do remember climbing the staircase into the tower and then onto the very steep little ladder that led all the way to the “widow’s walk”. At the top was a little hatch, and we were able to stand on the very top of the tower, which afforded us a magnificent view of the surrounding area. We were probably lucky that we didn’t get arrested!

07/14/2017

if you gentlemen are shopping for a Conservation expert…. allow me to offer services to you..

https://www.facebook.com/DonzineConceptDesign/ thank you or simply call 305 790 9214 and leave msg or txt…. Good day…

09/19/2017

Today I googled this house after reading Lionel Shriver’s book “A perfectly good family” which is all about this house. I’ve read most of Lionel Shriver’s books but was late reading this one. It was wonderful to find all this information about the house after finishing a book I really enjoyed and didn’t want to end. Wonderful photos. Thank you Ian! And Lionel Shriver!

07/19/2019

I love all these pictures! really appreciate your site as a young newcomer 2 raleigh who keeps noticing all the amazing old buildings around town! this house made me stop in the middle of the road to look at while driving aha. thank you for your work!

09/21/2019

I posted this in the “Raleigh Boy”‘s blog page, but thought I’d share it here, also:

Thank you so much for relating this history of the house and its final occupant. My dad worked for the NC Department of Health in the Bath building behind the house in the early 1970’s. I would occasionally visit him at work, and fell in love with the house as soon as I saw it. I loved the Munsters and the Addams Family (still do!), and stories about haunted houses, and this house looked just like it would be the perfect residence for any of them!

The yard was completely overgrown with trees and weeds. So much so that from across the street just about the only part of the house you could see were the steps of the porch, barely visible from the shade of the trees, and the top of the tower sticking up over the treetops. The windows were so dirty, and looked like they were blocked with stuff piled high, that you couldn’t see in them at all. The back left side porch had been enclosed with windows with small square panes, and looked like it just fit the bill to be Morticia’s greenouse room. The other back porch on the right was almost entirely buried in wild grapevines.

The secretaries in my dad’s offices in the Bath building told me they used to see the old lady, with make-up they said looked like baking powder, walking her little dog.

I was so enamored of the house and feared it might be torn down that I drew a picture of it and sent it to the mayor (don’t recall his name, but do remember he was the first African-American mayor of Raleigh), with a note telling him how I hoped the house would be restored and not demolished. He wrote me a reply saying my drawing was so good he recognized the house immediately, and was glad to know I had an interest it being saved. (I so wish I made a copy of that drawing before I mailed it!)

Once again, thank you so much for researching and sharing what you found out about that mysterious old lady my dad’s secretaries told me about seeing.

P.S.: I have some photos I took back in the 1970’s I can send you.

http://goodnightraleigh.com/2011/10/reminiscences-of-a-raleigh-boy-part-7-the-ghost-of-blount-street/

03/18/2022

14v7588u

04/03/2022

o1b95dha

08/13/2022

6mbleu

03/28/2023

What i don’t understood is in truth how you’re no

longer actually much more smartly-appreciated than you

might be now. You are very intelligent. You understand therefore considerably in terms of this subject, produced me individually imagine it from a lot

of various angles. Its like women and men don’t seem to be involved until it is

something to do with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs great.

All the time handle it up!

02/14/2024

2a8bv2

03/03/2024

nvktuk

03/28/2024

52cqnz

04/20/2024

t8m51u

04/29/2024

x177d3

04/30/2024

vdcyy3

05/13/2024

sqmxi6

05/25/2024

c58ey3

06/11/2024

r4yzju