Raleigh’s Brutal Government Buildings

Two years ago, I declared the structure above, the Bath Building, as the Ugliest in Raleigh. While I had a change of heart not long after writing the article, it’s still pretty high on the ‘ugly’ list. It is the perhaps the most striking and textbook example of the Brutalist style of architecture. Brutalism is characterized by an imposing rectilinear shape, poured concrete, and sparse use of glass and steel as exterior features.

Raleigh has a plethora of these buildings. Most are in the dead zone, the strip of state government buildings around Blount and Salisbury Streets.

The Ministry of Love was the really frightening one. There were no windows in it at all. Winston had never been inside the Ministry of Love, nor within half a kilometre of it. It was a place impossible to enter except on official business, and then only by penetrating through a maze of barbed-wire entanglements, steel doors, and hidden machine-gun nests.

–George Orwell, 1984

Recently, someone drew the comparison between the state government buildings on Halifax Mall and that of the buildings described by George Orwell. If you’ve read the book, the connection between these buildings and those in the political-fiction masterpiece isn’t hard to make. The Brutalist Style was often associated with social Utopian ideals.

Part of this stems from a true-to-materials construction that wasn’t laden with excess in the form of decoration. Additionally, construction with poured concrete is less expensive than other building methods. This made it appealing to elected leaders spending taxpayers’ money on public buildings.

Raleigh’s Ministry of Love

While the Bath Building is far from the depiction of the Ministry of Love in 1984, the lack of fenestration and imposing nature aren’t that far off, either.

Someone involved in the planning and design of the Bath Building commented on the previous article, and provided insight on its unique outer appearance:

There are no windows on the upper two floors because that is where the original labs and administrative functions were located. Windows serve no function in a lab, and wall space was maximized in this manner.

The curious inverted pyramid shape visible from the outside on the upper floors resulted from having to combine a basic laboratory module size with an office module size. It was necessary to rotate the upper floors 45 degrees to accommodate vertical structural elements not being in the middle of halls or rooms. So, in this case the exterior is purely a result of form following function. And believe me, we did take a lot of flack in the early days too. But it is what it is..and has served the citizens of North Carolina well.

–Bill McDowell

The Ultimate in ‘Form Follows Function’

Although the term Brutalism is associated with a ‘brutal’ form, the word originates from the French term béton brut, meaning raw concrete. It was used by modern architecture pioneer Le Corbusier to describe many of his buildings. Although it differs substantially from the International Style of modernism, it shares many of the same tenets of the modern movement.

The exteriors of these buildings often reveal the use inside. Concrete lines and shapes often reflect interior structural elements. This is in addition to the exterior itself functioning as structural support. Without decorative elements or a focus on making it “pretty”, poured concrete buildings may be the ultimate in form following function.

The AT&T Building: One of the Earliest Examples

Although not a government building, one of the earliest buildings in Raleigh in this style is the AT&T Building near Nash Square. The concrete exterior served to shield the electromagnetic equipment inside. It was built so that telecommunications systems would continue to operate in the event of an attack or other catastrophic event. With no windows, it is an ominous and lifeless tower.

Replacing a Historic Neighborhood with Brutalism

In the 1960s through the early 1970s, North Carolina state government was consolidating the location of administrative buildings in the area north of the Legislative Building (1963), between Salisbury and Blount Streets. The latter was at one point Raleigh’s most exclusive neighborhood, and it was decimated by the state’s plans for an expansive governmental complex.

The state bought up properties and subsequently demolished them, forever destroying many of the grandest houses in Raleigh. You can see this today with numerous old stone walkways that lead to surface parking lots. The end result of the state’s destruction is a dead zone, an area that is deserted during non-business hours.

After the dust settled from the state’s wanton destruction of these historic homes, a few were relocated to Blount Street from other areas in order to preserve them. The Capehart House (above), the Merrimon Wynne House, and the Lewis-Smith House are a few examples.

There are a few exceptions to the sea of gray government buildings. One is the 1861 Seaboard Railroad Office Building, above. It was saved from the wrecking ball and moved from its original location in the mid 70s. It is now a just few blocks away on Salisbury Street.

The grand historic homes on Blount Street are now for sale, and the Blount Street Commons project aims to breathe new life in to the area.

Other Examples of Raleigh Brutalism

Wake County Court House

A beautiful Beaux-Arts Court House dating to 1915 was destroyed to make way for this imposing and aggressive tower. It doesn’t exactly instill the kind of feeling you want before walking in to court.

North Carolina Records Building

The Wake County Jail

The building most suited for the Brutalist style is the Wake County Jail, to the rear of the Sheriff’s Department.

Albemarle Building

The photo above gives the impression that there are more sources of natural light than there actually are. On its longest sides, the archdale building is a vast expanse of a color somewhere between drab gray and white.

The Most Loathed: Harrelson Hall

It comes as no surprise to anyone that’s been in it that Harrelson Hall has several significant shortcomings.

In 2001, a report making the case for a new math building on campus summed it up this way:

Harrelson Hall suffers from major architectural flaws that include: classrooms serving thousands of students each day being immediately adjacent to faculty offices; a poorly designed hallway system [with] intractable problems [of] noise and congestion; unresolved difficulties with heating and air conditioning; external stairways that are neither heated in the winter nor cooled in the summer; no public elevators; no public restrooms in the main part of the building; ad hoc telecommunications wiring; inadequate electrical wiring; an almost total lack of meeting and conference rooms; and no commons areas.

Although initial plans called for the destruction of Harrelson Hall, it appears that has been delayed indefinitely with the construction of SAS Hall.

Brutalism Doesn’t Have to Be Ugly

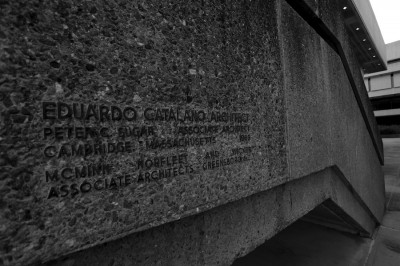

The Greensboro Municipal Building was designed by Eduardo Catalano, former head of the Architecture Department of NC State’s School of Design.

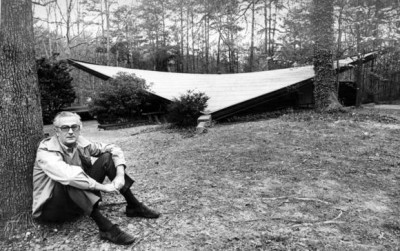

Far removed from his legendary hyperbolic paraboloid house in Raleigh, Catalano proved that poured concrete doesn’t have to ugly.

With the destruction of the Raleigh house in 2001, this is his only remaining building in North Carolina.

Modernist pioneer and Harvard Professor Marcel Breuer described Catalano as ‘one of his best students’. Breuer later became a prolific proponent of the Brutalist Style, so it’s not that surprising that Catalano would follow in the footsteps of his former mentor when incorporating it in to his own designs.

Not Going Anywhere Any Time Soon

There are many buildings of this style currently at risk of demolition in many other cities. Brutalist buildings routinely rank at the top of ‘most hated buildings’ surveys.

Over time, they become even less appealing. The concrete cracks and decays. The surface becomes discolored and easily stained.

Raleigh has lost modern architecture icons such as the Garland Jones Building and the Catalano House, and others are at risk (Milton Small’s Municipal Building). Unfortunately, their Brutalist cousins are here to stay.

Related Articles

- Reminiscences of a Raleigh Boy, Part 1: The Blount Street Saga

- Harrelson Hall and its Ultimate Demise

- The Bath Building: Ugliest In Raleigh

- From Treasure to Trash: The Demolition of the Wake County Courthouse

Further Reading

- The “Brutal” Wake County Court House (New Raleigh)

- In Defense of Brutalism

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

09/02/2010

Fantastic article! Every bit of it needed to be said. But I’ll tolerate all of the “uglies” if we could just get rid of the Archdale Building. Rumor has it that it was its architect’s way of giving the finger to Raleigh after he didn’t get the Art Museum commission. I don’t know if that’s true, but it is without doubt the epitome of a hive for worker bees that looms over Peace College like the hammer that’s waiting to come down. If there were ever a case for implosion, this is it!

09/03/2010

I’ll take working in Archdale and looking out over the mall and legislative building every day over working in the Parker-Lincoln Building (2728 Capital Blvd), where the rest of DENR is housed. Talk about a hopeless environment, and P-L is the epitome. Archdale is merely inconvenient by comparison.

09/04/2010

I disagree, John. Aside from Harrelson, I think all the buildings you highlighted are quite nice. The Archdale building is especially beautiful. I’d take more of this style anyday than the god awful bland cookie-cutter contempo-condo style sweeping the city. Brutalism at least has an ethic, and at least these buildings add a sense of drama to the cityscape; I think you’d be hard pressed to come up with even a few new buildings that are in any noticeable way visually interesting.

09/05/2010

Another great post, especially the etymology of the term Brutalism.

09/06/2010

Say what you want about Brutalism, but at least it’s an ethos, Dude.

I agree with Sid 100%, at least there’s some soul there. All these new buildings in Raleigh are so determined to no offend or inspire anyone, and they just end up being uninteresting. They look like they were just put there to make a developer money. All these old buildings at least have a cultural or artistic subplot, some sort of character that speaks to the values of that time and shows that the building itself was just as important to the community as it’s use.

09/08/2010

i interviewed for a job in the bath building nearly 20 years ago. the job was nice, the potential coworkers were nice, but the building was so depressing that i took my name out of consideration for the job immediately after the interview. what a miserable place to work.

09/25/2010

The ugliest (UGLIEST) building I have ever seen is this one:

http://maps.google.com/maps?q=verizon&f=l&sll=40.450703,-79.938326&sspn=0.017308,0.045104&ie=UTF8&t=h&split=1&rq=1&ev=p&radius=1.42&hq=verizon&hnear=&layer=c&cbll=40.448819,-79.948061&panoid=jh2luzAwkvIMMhhia2xI1w&cbp=12,304.18,,0,-8.14&ll=40.448907,-79.9481&spn=0.001133,0.002819&z=19

It’s in Pittsburgh. I walked past it every day on my way to school and I swear I haven’t seen an uglier building in my life. It’s a Verizon office. The outside is covered in theses tiles that are the dirtiest shade of green ever. It looks like the entire building is covered in algae. The windows are tiny! I don’t know how I would tolerate working there if I did. Ughh, uggh!

09/26/2010

Great article and interesting read. I’ll have to add my name to the very short list of dissenters on the Archdale Building, though. While it isn’t exactly a thing of beauty, the geometry is unique enough to stand out, particularly from certain angles. The blandness of the surrounding structures on that end of downtown leaves the Archdale Building as the lone landmark on the skyline there.

I like the Orwellian references. It’s going to be impossible for me to separate it from “Brutalism” wherever I see it now.

10/26/2010

I, for one, have always thought the Bath Building to be quite striking, if not exactly beautiful. I think it is a terrible shame that it and many of the other government buildings of that era in that part of town displaced historic homes, but now that that milk has been spilled, it is what it is. I think the Bath Building makes a particularly interesting counterpart to the incredible Heck-Andrews directly behind it. I’ve heard a lot of people say that they find that juxtaposition jarring, but I think it’s quite dramatic.