Reminiscences of a Raleigh Boy, Part 7: The Ghost of Blount Street [Updated]

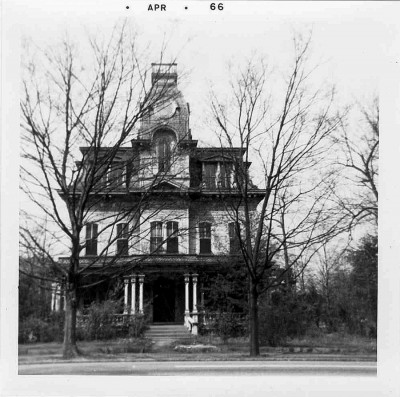

The year was 1966, and the gilded luster of the aged grande dame had faded long ago. With great trepidation I walked up to the front door. My buddy and I had been roving Blount St. for more than a year by then, exploring and photographing the once elegant mansions being demolished by the state in the late 1960s. And of course I always had my trusty Kodak Instamatic camera in tow.

The flamboyant Heck-Andrews House, with its faded and peeling yellow paint, rotting ornament, overgrown and weed-choked yard — and especially its decadent grandeur — had always fascinated me. I wildly wondered what fantastic treasures could possibly lie within! By looking in a Raleigh city directory, I learned the house was owned by Mrs. Julia Russell.

‘Knock, knock, knock’ on the heavy, leaded-glass oaken door — a grizzled old woman with coke-bottle glasses peered suspiciously from around the partially opened door. We introduced ourselves — “Hello Mrs. Russell” — and politely asked if we might see the interior of the mansion. “I don’t let ANYBODY in my house!” and she promptly slammed the door in our face. So that was the end of that — or so I thought.

Encountering a Shadowy Enigma

Several years later, by then in my 20s, and ever engaged in my downtown explorations, I encountered on several occasions a curious older woman who had the appearance of a ‘bag lady.’ She always wore a black cloth ladies’ hat, a plain black dress, and an overcoat — even in the warmest weather. Her hair was dyed shoe-polish black and her face was heavily powdered in white pancake makeup; her lips were thick with ruby red lipstick. I soon learned this intriguing woman was Miss Gladys Perry.

The Youthful Gladys Perry

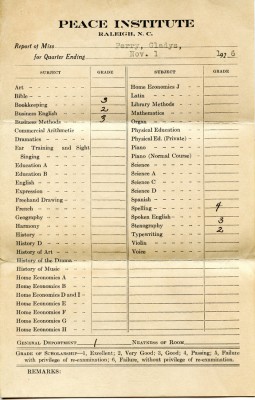

The old woman with the coke-bottle glasses whom I had encountered in 1966 was Gladys’ mother. Gladys was born to Julia and Henry Perry in 1907; before her fourth birthday in 1911, her mother had been widowed. Mrs. Perry later married Robert Russell, and by the mid-1920s, the family was living at 516 N. Person St. Gladys was a student at Peace College at the time, enrolled in the business curriculum.

Nicknamed ‘Shug,’ a diminutive for ‘Sugar,’ (also spelled ‘Sug’ or ‘Suge’) Gladys apparently was a well-liked young lady in the 1920s. She had many friends, went to movies and dances, and regularly attended Edenton Street Methodist Church. She also loved to cook and sew, and she wrote poetry. Gladys also had at least four suitors during this decade.

I Love You

I love you when you’re laughing

I love you when you’re sad

I love you when you’re teasing

And I love you when you’re glad

I love you when you’re fooling

I love you when you’re true

And the reason that I love you

Is just because you’re you.— Gladys Perry

By the early 1930s Mrs. Russell was taking in boarders in the family home on Person St. Before the decade was out, Mrs. Russell once again found herself a widow. Gladys’ older brother Clark had married and left home to start a family; Gladys herself was employed as a typist and stenographer by the NC Division of Motor Vehicles.

In 1948 Mrs. Russell purchased the Heck-Andrews house from the Andrews heirs, who were probably very happy to unload the aging and decaying behemoth. And daughter Gladys moved in with her mother.

Gladys Perry, the Enigma

After 1948 there follows a gap of 25 years in what I know about Gladys, but she apparently retired from the DMV in the early 1970s.

This is where the story picks up.

Nearly every time I went downtown in the 1970s I would see the phantom figure of Miss Perry rummaging through trash barrels set on the street for pickup. I have no idea what items attracted her attention, but she always seemed intensely focused on selecting her acquisitions.

Gladys seldom spoke as she wandered through downtown collecting her treasures. The story goes that she powdered her face white believing people would think she was a ghost and would leave her alone. It was rumored she also carried a gun on her person for protection should anyone dare accost her.

As the years went on, I saw less and less of the mysterious black-clad figure with the ghostly white face.

By the mid 1980s, Gladys was spending less of her time roaming the streets of downtown Raleigh and more of it roaming the lonely and emotionally empty rooms of her Blount Street mansion.

The State of North Carolina vs. Gladys Perry

In early 1987 a Raleigh Times article announced:

The state will condemn the historic Heck-Andrews house on Blount Street because its unsafe condition poses a danger to the elderly woman who lives there and to nearby chemical labs… the state will seize the property through its power of eminent domain, and will relocate the resident, Gladys Perry. … the home [is] virtually without heat and electricity, since her utility bills are only a few dollars a month. … Miss Perry couldn’t be reached for comment.

Gladys’ mother, Mrs. Russell, had apparently died sometime in the 1970s. She left no will, and the mansion passed to Gladys and her brother Clark.

Since the mid 1960s the state had been systematically buying up the properties in the Blount Street area, intending to transform the acreage into a state government office complex. Most of the Victorian structures were demolished and paved over as surface parking lots. Only a handful of the grandest homes were spared, and were re-purposed as state office buildings. By 1985, the Heck-Andrews House was the sole survivor remaining in private hands.

Gladys’ brother agreed to sell his half ownership to the state for $84,000, but Gladys remained steadfast in her refusal to sell. She refused to even discuss it with state officials. (Gladys claimed it was she who had bought the property in 1948 and had recorded it under her mother’s name. But as Julia Russell’s name was on the deed, Julia was recognized as the legal owner.)

During her two-year battle with the state, Gladys’ health began to seriously deteriorate. She seldom left the house now, and state workers in the neighboring office buildings who were familiar with the shadowy figure began to worry.

By the late 1980s, Gladys inhabited but a single room in the 5,000 square foot mansion. (Photo by John Morris)

Snow began to fall one afternoon in January 1987, and a concerned state employee went to check on Miss Perry. She had not been seen for days. As there was no response to repeated knocks at the locked front door, the police were summoned.

The police went around to the back of the house, jimmied open one of the windows, and climbed in. They were amazed at what they saw. Trash and rubbish from Miss Perry’s forays were piled chest-high throughout the house. There were old calendars, books and stamps, a pair of silver-glittered dancing shoes and old clothes, spoiled food and every other odd and end one could imagine. Narrow aisles and tunnels through the trash offered the only passage through the rooms.

The police snaked through the trash passages and finally found Miss Perry in her second-floor bedroom behind a six-foot trash heap. She was huddled under blankets in the frigid house. … Sick, she was unable to move from her bed. Rescuers … saw blue and red streaks running up her feet and legs.

She refused treatment and would not let them take her to the hospital.

–Â Kathleen Christian, columnist, The Leader, November 1988

Ultimately the Good Samaritan state employee persuaded Gladys to see a doctor. She lost several toes to frost-bite and the early stages of gangrene had set in.

Gladys was later resettled in a small apartment in Raleigh, where she died a few years later. Thus, the state had won its battle against Gladys Perry.

Following Gladys’ eviction from her home, the state began the onerous task of disposing of her belongings. An enormous plywood chute protruded from one of the upstairs windows and workers unceremoniously tossed tons of her things down it into a huge industrial trash dumpster waiting below.

Ever curious, I used to go up there and poke around, hoping to find a way to get inside the empty mansion. I was unsuccessful in gaining entry, but one day I did find lying beside the dumpster a broken-open box — the contents of which lay strewn about on the ground. I made a quick inspection of the contents and was astonished at what I found. To the state of North Carolina the items in the box were merely trash, but to me it was treasure. I scooped up the box and ran home with it cradled in my arms.

The Box

I could not believe what I discovered in ‘The Box.’Â Its contents revealed nearly every detail of Gladys’ life over the course of two decades from 1922 until the early 1940s. I found hundreds of items as mundane as utility bills, her pay stubs from the DMV (Gladys’ pay for the month of October 1937 was $60), typed and handwritten recipes (Tuna Fish Sandwich Spread and Easy Meringues, for example), a receipt for a purchase of film from Daniel’s Camera Shop, greeting cards, handwritten prayers and Bible quotations, notes to herself to buy fabrics (“3 1/2 yds lace for slips. Ask at Boylan Pearce”), her 1926 report card from Peace College (her worst mark was for spelling — ‘passing.’) and dozens of newspaper clippings from the N&O, including poems, recipes, movie ads and political cartoons.

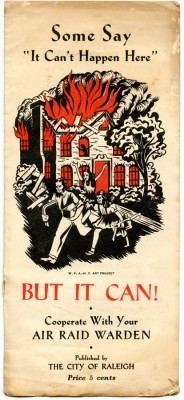

The Box also contained a wealth of far more interesting items than just the mundane — such as Gladys’ handwritten poems and musings on love, a pair of 3-D movie glasses (a souvenir of the 1939 NY World’s Fair), and a WWII pamphlet instructing Raleigh residents what to do in case of an air raid.

This pamphlet provided detailed instruction on how to prepare one’s household for an air strike, and what action to take during it.

Printed on the back of this pair of 3-D glasses: “This viewer is a souvenir of your visit to the Chrysler Motors Exhibit at New York’s Wold Fair.”

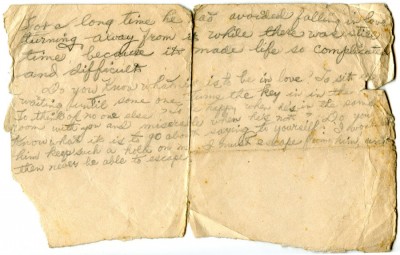

Below is an example of only one of the dozens of Gladys’ musings I found in The Box:

For a long time he had avoided falling in love

turning away from it while there was still

time, because it made life so complicated

and difficult.

Do you know what it is to be in love? To sit up

waiting until someone turns the key in the [illegible]?

To think of no one else? To be happy when he is in

the same room with you and miserable when he is not?

Do you know what it is like to go about saying it to yourself:

I won’t let him keep such a hold on me. I must escape from him,

and then never be able to escape.

However, the most amazing find among the heaps of ephemera were the love letters sent to Gladys by four suitors over the decade 1922-1932.

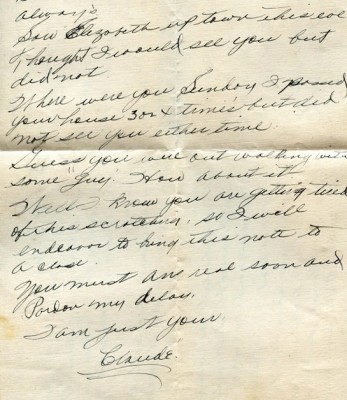

Claude Pearson fell in love with Gladys in 1922, and was the author of several amorous love letters to her. He usually began with “Dearest Darling,” and spoke quite ardently of his love for her, sometimes closing with “Your future hubby.” Apparently, though, it was an unrequited love.

In October 1922 Claude wrote:

Where were you Sunday? I passed your house 3 or 4 times but did not see you either time [sic].

Guess you were out walking with some ‘guy.’ How about it?

By June of 1923 the pair had apparently broken up, as Claude wrote a rather terse note to “Dear Miss Perry,” asking for the return of a photo of himself he had given her — and signed it with his full name: Claude N. Pearson

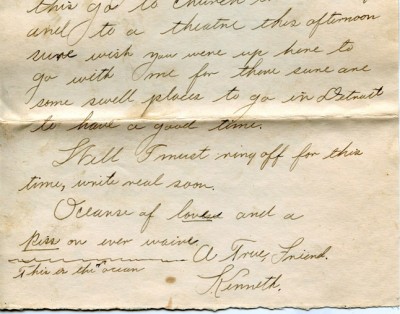

Then, in 1924, Gladys was seeing a young man named Kenneth, who seemed to live and breathe Gladys. He would often end his letters with “Oceans of love.”

…and [went] to the theatre this afternoon. Sure wish you were up here to go with me for there sure are some swell places to go in Detroit to have a good time.

Well I must ring off for this time, write real soon.

Oceans of love and a kiss on ever[y] waive [sic].

A True Friend

Kenneth

I love Kenneth’s annotation: “This is the ocean”

Curiously, in this 1924 letter to Gladys, he begged her to not let her mother know he had written her. Perhaps because theirs was a ‘long distance’ romance?

Dearest Gladys,

…I hurry home every day to see if any mail has come for me, and when I am expecting a letter from you it makes me hurry home that much faster. …

Dear I must close my letter but not my love for you. Write me real soon.

From someone who loves you

KennethPS. Listen Dear:

Please don’t let your mother or Clark read this. Destroy it when you read it. For they might get mad and stop you from writing to me and that would break my heart. So be careful Dear.

Just lots of extra love.

In the same letter, Kenneth pleaded:

Gladys, please don’t have your hair bobbed, for your hair is real pretty and you will be sorry after you have had it bobbed. All the girls up here are sorry they had theirs bobbed. So take fool advice and don’t do it.

Later, in 1927, Gladys was seeing a young man named Jimmie Page, a local boy who had moved to Warsaw, N.C. for his job. This relationship lasted the longest of the four — 1927-1933. In a letter to his sweetheart in 1927, Jimmie lamented that his job kept him away from her.

(Mid-Night Blues)

Gladys My Dearest

…I haven’t slept any to-night at all. I’m not even trying because I know there isn’t any use. I had planned for two weeks to surprise you. Now I had to have my plans all broken up. Gee it is tough. Dearest, life isn’t worth living no way if you can’t see and be with someone you love. …

Dear heart, please remember that I love you and always will whether I ever see you again or not. …

Sleepless nights I’ve laid awake all because of you. Jimmie loves you Dear.

Your own Jimmie

Their exchange of letters continued in a similar vein over the next five years, but they never married, and by 1933, the tone of Jimmie’s letters was more of that between friends than lovers.

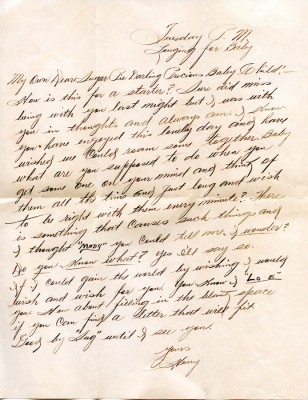

Finally, Henry appeared on the scene in 1932. Gladys was 25 years old. And yet another young swain had been smitten by her allure.

Longing for my Baby.

My Own Dear Sugar Pie Darling Precious Baby Child!

How is this for a starter? Sure did miss being with you last night but I was with you in thoughts and always am. …Baby what are you supposed to do when you get someone on your mind and think of them all the time and just long and wish to be right with them every minute?… You know I ‘LO_E’ and wish for you. How about filling in the blank space if you can find a letter that will fit.

Good by[e] ‘Sug’ until I see you soon.

Yours, Henry

And this is where the letters stop.

I found this photo of a young woman in The Box. Could it be an image of our Gladys? There’s no way to know for certain, of course, but I would like to think that the pretty and stylish ingenue seen here is indeed she.

However, the image of the Gladys Perry I vividly do remember, that of a reclusive old woman, her face powdered white, with ruby red lips and shoe-polish black hair, will always be fixed in my mind; for she will forever be the Ghost of Blount Street.

[UPDATE]

Following a tip from a GNRaleigh reader, another reader has located a photograph of Gladys Perry! He found it in the 1927 edition of Peace College’s yearbook, ‘The Lotus.’ She bears a striking resemblance to the ingenue pictured in the photo I published with the story. But of course, I cannot be certain the beguiling young lady seen in the earlier photo is for a fact Miss Perry, but I do know the one seen below is indeed she.

Note: Unless otherwise credited, photos are by Raleigh Boy

Special thanks to Ian F. G. Dunn

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

07/01/2013

I remember both oak trees. The Henry Clay Oak, as I knew it, had one branch that extended across North St to above the Heck-Andrews yard. The oak in your yard lost a large limb when Hurricane Hazel passed through Raleigh in 1954. That was the beginning of its end. I was there some years later when a bulldozer pulled the de-limbed trunk over with a cable. I used to climb in the Magnolia tree and the Crab Apple tree between it and the Holly tree. And how I love the memory of the Daffodils—one bed near the Holly and another on the Wilmington St side of the house.

Randy

07/01/2013

Thank you for reminding me I had not thought of the daffodils in years. We all climbed the Magnolia tree at one time or another. It is still there not as pretty as it once was. If I remember right when the limb fell off the Oak it damaged it in addition to the crepe myrtles that were on the property and completely demolished the Japanese flowering plum. The fallen limb was larger than the Magnolia in diameter and what a wonderful time we all had playing on it.

I googled Hubert and found Dixie Kay. I am so sorry to hear of their deaths. I knew Hubert had been ill but was quite surprised to see Dixie Kay’s obituary, she was always so full of life probably the most enthusiastic of all the kids I knew growing up. Please accept my condolences.

07/01/2013

Yes, of course. You are very kind to remember them. I was living in San Diego when Hu passed, but was able to tend to Dixie until near the end of her journey. Other relatives and friends were at her bedside when she passed.

But the Daffodils—what a joyful memory—bursting gloriously from the earth in neat rows like soldiers marching to meet the spring sunshine about Easter. I have thought of them many times.

And, finally, the oak limb also broke the concrete garden bench in two.

Randy

07/01/2013

I remember picking armloads of daffodils and handfuls of pansies and violets even dandelions. Magnolia was beautiful but would not last even a day when removed from the tree.

I believe the bench was hit by another limb. May have been at the same time but the bench was closer to the house and the massive limb was closer to North St.

I have looked for another bench like that one and never found one. I can find the curved cement bench but the two supports on that one had faces on them.

My daughter has been after me to write down childhood memories I had written down the monopoly game on your front porch. I had not thought of Spider and his biting. That’s why we need leash laws.

I don’t know what happened to the Duncans. I tried Google but did not find any of them

You know what is funny to me. My mom was Martha to most of the kids in the neighborhood. I always called your mom Sarah Frances. but your dad was Mr. Gill. I guess it was because Mom’s were around more and your dad was at work.

I think it was Raleigh Girl who mentioned Mr. Knowles and the auctions. I do not know if an auction was held at 105. I do know Tractor Trailer Trucks were loaded and furniture and most everything else was loaded and sent to auctions in New York. Martha’s older sister and her husband did all that and sold the house, too.

Well I guess we have hogged the comments long enough and it is time to let others get a word in edgewise.

I have a picture of the house when it was in its day if I figure out how to send it to Raleigh Boy and if he will post it can you get it or do you still want it?

07/02/2013

One body part that works better than ever for me is my forgetter. I defer to your memory, except for Spider’s leash. Annette was certain he was leashed at the time. She just misjudged its scope, but she was well warned of the danger. I do not recall any talk of an auction.

I would love to have a copy of the picture. If Raleigh Boy posts it, that would work. If not, I would be most grateful for you to send me a copy. We can arrange the means later, depending on what he does. I have googled every which way I know to locate one, but to no avail.

Yes, pitch in one and all. I am pleased to retire.

Randy

07/02/2013

Randy,

I see no way to post a picture. here is my email

105eastnorth@gmail.com

Gee, very original isn’t it. It is easy to remember though

11/10/2013

I have a pic that I took of the front of the Heck-Andrews and it there is a very clear image of a man with a bread standing at the window. I watch to assure you that I’m not a lunatic and if you can give me an email address or whatever as to where I can send this pic too I will definitely do so. Plus I’d to know if anyone can figure who this guy is. He looks like Johnathan Mcgee Heck to me personally but I’d love to have other opinions please email me dreamjeanie80@yahoo.com

Thanks for your time,

Jeanie

11/12/2013

I want to apologize for all the typo’s that my last message had but I was using my phone and was visiting my friends and that caused me to be distracted and my phone itself made me look like I was a 3 year old typing.

I do have a picture of the side of the house and in the pic it shows a image of a man with a mustache and what appears to be a full apparition of a man. I have a friend in law enforcement in Wisconsin I sent her the picture and she is going to have someone clean it up for me and try and remove all the pixels to see if we can clearer view of what it really is.

If anyone would like to see if for yourself please email me I’d like to see if we can either debunk it or figure out who it is.

Thank you for your time,

Jeanie

11/19/2013

Thank you for your story! My dream is to buy the house with my friend (yes I realise its owned by the state) and renovate it. It’s the prettiest house on Blount street without a doubt and currently it’s in need of repair. I’ve always wondered who lived here and it’s awesome to figure it out. The love letters are beautiful and makes me wonder about how beautiful she must have been. The story of her hording in a sad one. My grandmother is a horder so it’s easy to imagine what the house looked like. I can garantee you that the house will never look like that when I own it!

11/19/2013

I always enjoy catching up on the stories, here. I love that this blog post still gets lots of readership, and new experiences of the house are shared. I love that place, still.

02/05/2014

I loved this article. Growing up this house always AMAZED me. I am proud to say that I got the chance to see her too. I would love to have my Family’s portrait taken there.Who would I contact to see if it is possible. Thanks, rbn.lynn66@gmail.com

02/21/2014

Thank you for doing all this work. I found this quite interesting. My family is from the Raleigh area – at least my grandparents and at one time my Great grandfather worked for the Andrews Family. Just before they were getting ready to settle the house someone called and left a message about a picture of my great grandfather (I believe), but because no one was available I guess the picture went to trash or archives – who knows. Anyway, reading this story help me to sort of imagine what it was like for my ancestors to work there.

Thanks again for taking the time to write their story and for keeping the Andrews Family memory alive.

Good job!

02/21/2014

June,

Which branch of the Andrews family did your ancestor work for? I remember James Philips who worked for A.B.Andrews,Jr. And heard names of some of the other employees. I do not know anything about pictures but if any went to archives I am sure you could get a copy if you would like.

05/03/2014

Thank you for this story! My husband and I ended up at the Heck Andrews house on our 1st date 25 years ago! We both love history and architecture, and both had been drawn to the home. As a Raleigh native and graduate of Peace myself, it is interesting to know that part of the history, I have seen Gladys but did not know who she was. My husband is a trained historical renovator and has worked throughout Oakwood, Cameron Village, etc. and had like so many of you, knocked on the door when he was younger. I cannot wait to share the article with him!

Isn’t it amazing just how many people are “drawn” to this home? I love all the homes downtown, but this one calls to me!

05/16/2014

I’m so glad I stumbled on to this very informative article of the Heck-Andrews House. My mother worked at the Bath Building and for a time, would pay the old lady that lived there (“Ms. Perry” she called her) to park around the back of the house. To my knowledge, she never saw her much- just paid her parking rent and once a year, gave her a Christmas card. My mother did say that when she was moved out, she was shocked with the rumors at the amount of trash they found in the house- mountains of newspapers and magazines piled ceiling high- many, many years worth. I could see how the state felt it was unsafe and a fire hazard, especially in such close proximity to the Bath Building, which housed state labs.

As a child, I would occasionally go to work with my mother, and I was absolutely fascinated by this house. I always thought it looked like a dollhouse, albeit a rundown one. I remember the grounds being very overgrown and the house seemed so lonely.

However, like everyone here, it drew me in, and I was so relieved to know that the state wasn’t going to tear it down. I didn’t even know it had an official name until the historical marker was posted out front. Even now, I slow down and take it all in when passing by. I hope one day, I’ll get the opportunity to go inside.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading all the accounts here of this marvelous house, and it’s interesting inhabitants! Thanks to all!

09/09/2014

What a great read! Thanks for posting the information and the photos. I moved to Raleigh in 1989 and quickly fell in love with this house. I do hope that the state of NC will soon decide to sell this house before it is too late to save. Too many memories of one of Raleigh’s grandest homes to go to waste.

09/26/2014

I was the Asst. Manager at the Goodwill on Hargett St. In the early 80’s I remember a woman coming into the store, She wore… I think it looked like a wool black or dark grey coat, her hair was a matted wig that seemed to be a bit crooked every time I saw her. If I remember correctly she had white powder on her face. We referred to her as the cat lady. Could this have been Gladys? I also had driven by this house many times being I was raised in Raleigh and always admired the beauty of this and the other homes in the area. Thank you for sharing.

09/26/2014

I only saw Gladys wear knitted or crocheted hats. I never saw her wear a wig. Although the white powder sounds like Gladys.

There was another old woman in Raleigh who was known as the ‘Cat Lady’. They were about the same height and could not determine their age. I do not know where she lived but you could smell the cats if you were within ten feet of her.

09/26/2014

I remember that she did have a rather strong odor. Maybe this was not Gladys. Thank you

02/04/2015

My mother (she died in 1999) told me as a young lady she rented a room in this house. I’m trying to determine exactly what years the owners would have rented out rooms. My mother was born in 1927. I, too, have always loved this house. And yes, having grown up in the Oakwood area my brother and I would walk over after delivering The Raleigh Times in the area and stare at the house and occasionally knock on the door. Once we swore we heard a small dog barking inside. Does anyone know what years it was a boarding house? To know my mother once lived there is awesome!!

02/05/2015

Having grown up in Raleigh, all of these beautiful old homes captivated me from an early age and I remember reading of the condition of this house when the state took it over & the final monetary settlement.

My mom & brother lived in the Capehart-Crocker house before it was relocated. My brother said he’d climb up on the roof to star-gaze, and they were there when Hazel hit. My mom told me that the landlord of the house at that time was so slow in doing the debris clean-up afterwards, mom wound up taking a hand saw to cut up the tree limbs that were blocking the clothesline.

Randy Gill — Your mention of the ladies’ bed & board run by Mrs. Faison caught my attention. My mom told me that she lived at a women’s boarding house when she was working at the Broadway Café on Hillsborough Street when she met my dad. When my parents got married, they were sitting on the steps of the boarding house & mom had to go up to her room & get the marriage certificate to prove he had a reason to be there. I wonder if Mrs. Faison’s could have been the house…

Great article, Raleigh Boy!

02/05/2015

Mrs. Rogers was Gladys Perry’s mother she bought the house when Mr. Andrews died. That would have been the owner when it was a rooming house.

I believe Mrs. Faison had the house on the other corner North and Wilmington St. She had a very smooth walkway from the sidewalk to her house. When it rained the walkway was slick as glass. When it was wet we would slide on it znd usually fell. Mrs. Faison would come out on her porch and fuss at us and tell us to leave. I believe the awning she had to shade her porch had an F on it.

The Capehart house was on Wilmington and it was cut up into apartments. I remember a few of the people who lived there in the 50’s and 60’s

04/09/2015

This is the mansion! The French Empire architecture that ingrained and burned inside my soul as a child. Visiting the capital on a school trip. I must have been around 8yrs old. The bus circled around on Blount St. and we passed the massive yellow paint peeling, grey scalloped shingles, curved wooden banister stairs, shutters hanging, dilapidated house. I fell in love at first sight. It was the most impressive awe inspiring sight I had ever seen. The rest of the children on the bus were laughing at the spooky house, I was crying at the sheer beauty. Every year we would visit the capital. Begging bus drivers, teachers, chaperons….anyone who would let me peek again. As a teenager with my first car, as a young adult going to a job interview, as a young wife traveling with my new husband…drawn back to Blount St. Now the internet lets me visit again. I saw when the state took over. I was thankful they put up the rain gutters. The water damage was heartbreaking to watch over the years. I wasn’t too keen on the paint choices the historic society picked for window trim colors? My love of old world craftsmanship, 14ft ceilings, hardwood floors, crown molding, and everything old is because of this wonderful fantasy fairy tale building. Thank you RaleighBoy.

04/09/2015

I had to go by State Construction a few week ago and took a detour on the way back to jump up on the porch and look inside. Would be killer to see fully restored.

07/06/2015

It looks like the state is considering putting it up for sale in the near future.

http://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/state-politics/article25195528.html

02/25/2016

I’ve lived in the Raleigh area since 1996 and I just recently discovered this gorgeous gem of a house. I have family in Philadelphia, and the city hall there is also French Second Empire architecture. My most recent trip inspired me to look for places in NC of the same style. I was blown away to learn that this place is 10 minutes from where I live. It’s beautiful in photos, but it’s absolutely breathtaking in person. Whoever restored the outside did an amazing job, the inside just needs a little love. It’s for sale now, and I’m just a poor college student; however had I won the Powerball back in January I probably would have bought the house and had an expert restore, it with modern amenities of course. Maybe turn it into a bed and breakfast or open it to the public as a museum or something.

Also, the whole story of Gladys Perry is so wild, like a Raleigh version of Grey Gardens.

07/16/2016

My grandparents moved here in the 1930’s . I have always loved Raleigh & all of the history that is here . My father worked for the State of NC before all the “mall ” was developed so at a young age I brag an loving the architecture of our beautiful city . I saw lots of houses lining Blount St . And saw many in the process of being re-located when the state bought them & used them for office spaces . The Heck – Andrews house is such a great save and I have like reading about it ‘s history and the families/people who lived there . But it is sad about Miss Perry . I am so glad that this wonderful place is still here and people have taken an interest in preserving it ‘s beautiful charm . I hear that it can be rented for ocassions and if I ever get married again will make plans to rent it for a party ! I feel it would create some happy memories for the house and for me . This is my daughter ‘s favorite Raleigh home …. Thanks for posting the story , photos , and comments … I truly enjoyed reading !

09/14/2016

We moved to Raliegh 1970 as newlyweds. Rented 3room apt on Mortecai dr in a large southern old home owned by a Mr. Perry (relation?) there were two apartments on the second floor. We didn’t own a car so we walked everywhere! Many times walking by this house and a few others in the neighborhood. I will never forget the magical feelings walking by the homes on Person, Peace, and Blount street. And also the Govenors mansion.

Thank you for this article, it was such a nice walk in the past.

09/16/2016

We shared this link with our Facebook followers and thank you for your wonderful insight and remembrance of your earlier days in Raleigh and documenting this magnificent mansion.

Victorian House Lovers

BHM

10/10/2017

I worked as a Red Cross volunteer in the house next door..which was the Red Cross Chapter house. I never saw the woman that lived there; but there was always a ‘buzz’ about the office of her being alone. I used to fantasize about owning the Big House..I’ve always admired large roving old homes. Been holding my breath to see what the ‘state’ will make of it….

12/16/2017

I used to pass this house on the way home from work. I stopped once as there was a lady in the yard…wanted to go in ..thought maybe she would invite me. It has been decades since that day, but I remember her wig looked like a piece of carpet cut out and placed on her head…she seemed to be bald . This was probably at the last. It is heart breaking that she lived in such poverty so close to the governor’s mansion.

The house probaby was sad and lonely but when you think about it..there were many people who loved it from afar.

03/05/2018

I recently discovered the Blount Street area of Raleigh. I’m from Pittsburgh; my daughter is a student here. I’m reading everything I can, and following #olderaleigh on Instagram. The history of the area around the Heck-Andrews house is similar to the fate of so many mansions on Fifth Avenue in Pittsburgh. An enormous amount of money is needed for restoration, but it is so worth it. Preserve, preserve, restore for the future. Once it’s gone, it won’t come back. Are there volunteer orgs in Raleigh for folks like me?

09/21/2019

Thank you so much for relating this history of the house and its final occupant. My dad worked for the NC Department of Health in the Bath building behind the house in the early 1970’s. I would occasionally visit him at work, and fell in love with the house as soon as I saw it. I loved the Munsters and the Addams Family (still do!), and stories about haunted houses, and this house looked just like it would be the perfect residence for any of them!

The yard was completely overgrown with trees and weeds. So much so that from across the street just about the only part of the house you could see were the steps of the porch, barely visible from the shade of the trees, and the top of the tower sticking up over the treetops. The windows were so dirty, and looked like they were blocked with stuff piled high, that you couldn’t see in them at all. The back left side porch had been enclosed with windows with small square panes, and looked like it just fit the bill to be Morticia’s greenouse room. The other back porch on the right was almost entirely buried in wild grapevines.

The secretaries in my dad’s offices in the Bath building told me they used to see the old lady, with make-up they said looked like baking powder, walking her little dog.

I was so enamored of the house and feared it might be torn down that I drew a picture of it and sent it to the mayor (don’t recall his name, but do remember he was the first African-American mayor of Raleigh), with a note telling him how I hoped the house would be restored and not demolished. He wrote me a reply saying my drawing was so good he recognized the house immediately, and was glad to know I had an interest it being saved. (I so wish I made a copy of that drawing before I mailed it!)

Once again, thank you so much for researching and sharing what you found out about that mysterious old lady my dad’s secretaries told me about seeing.

P.S.: I have some photos I took back in the 1970’s I can send you.

09/21/2019

So sorry to read about Raleigh Boy’s passing. I wish I had sent my post years ago so he could have read it. Have a feeling we would have been (still are?) kindred spirits.

Even though we never met, I am so sad such a lover of preserving the past is with us no longer.

02/26/2020

The mayor’s name was Clarence Lightner. He was elected in the mid 70’s. They are an Raleigh family associated with the funeral business and other ventures

09/09/2020

The comments from Randy Gill and myself are talking about the Oak Tree that was in my grandmothers front yard at 105 E. North It was The House of The Oak. and belonged to A.B.Andrews older brother.

The comments I had put on for the Heck Andrews House have been deleted. I guess there was not room to keep them.

To Jessie Lanier. There was also a rooming house on North St that belonged to Mrs Perry. She made her own hats and paint pictures.

When A.B.Andrews died 10/21/1946 the Heck Andrews house was sold to Mrs Rogers. She turned it into a rooming house.

10/31/2020

This site has been so fascinating to read, just like the house itself.

Some time after the State finally took over the house, a friend of mine who had access got the key and took me inside for a tour. This was before any of the clearing out had begun. The place was still quite dark in the daytime, with most of the downstairs windows blocked, so my camcorder was hampered by the low light. Some rooms in the house had power, most did not.

This year I discovered some computer software which helped me enhance the old video I’d had on the shelf for years, and I put together the most usable parts of our visit. It was both sad and fascinating to see what the once grand mansion had become, and a great many rooms were simply inaccessible due to the piles of trash and accumulated clutter.

It’s quite a contrast to the feeling you get now, seeing photos of the restoration with all the rooms emptied out and flooded with sunlight.

I hope you will find this of interest.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCicVzrGTdI&ab_channel=RowellGormon

10/29/2023

I found this article with a video of the cleared out house. Here is the link to the video.

https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/counties/wake-county/article29762557.html