The Raleigh Building: the Short Story of a Tall Building

“The Raleigh Building, the Raleigh Building, that’s all he talks about.†My mother rolled her eyes as she lamented my father’s closing moments. She was right: until he bid his final good night to Raleigh, Bob Wollman was synonymous with the Raleigh Building. It was his dominion, just as it had been his father’s. From leaseholder to secretary, everyone in that building could count on him to cater to their needs and provide for their comfort in every season.

The whole business started on July 30, 1945, in the era of crank-operated adding machines and black rotary phones, when the partnership Wollman, Heyman and Katz bought the Raleigh Building for $350,000. My grandfather, Sidney Wollman (who built Grosvenor Gardens Apartments in Raleigh) managed the building, and word was that he also frequently managed to upset just about everybody in it. Nevertheless, he presided in grand style.

He hired two of the best-looking black women in Raleigh, Leola E. Lee and Mabel Smith, to drive the stick-shift elevators, and outfitted them in well-tailored, brass-buttoned navy uniforms. Bernard Rogers polished the brass elevator doors in the lobby every night

and kept the terrazzo floor shining. A few fingerprints on anything were reason enough for my grandfather to summon the painters. His partners Lazarus Heyman and Perry Katz, developers in Danbury, CT, were always alert to every item on the monthly reports from their Raleigh investment. A $35 expense for the 1945 office Christmas party brought this terse inquiry from Mr. Heyman: “We note a $35 expense for the office party. Did you have Jayne Mansfield appearing in person, or just what was the pitch?â€

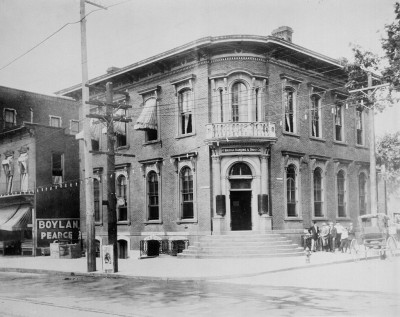

The site of the Raleigh Building, the southwest corner of Hargett and Fayetteville Streets, held the first permanent home of the Raleigh Banking and Trust Company, which was founded on September 12, 1865 just months after the Civil War ended. Nicknamed the “Round Steps Bankâ€,

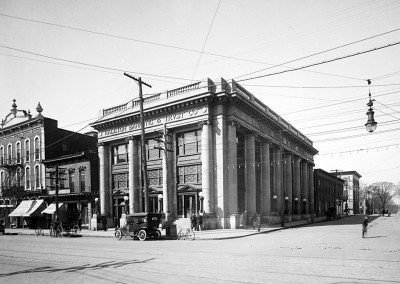

that structure was replaced in 1913 by a 3-story Neo-classical Revival structure (below) designed by Atlanta architect Philip Thornton Marye.

The building was engineered for the additional stories: you can feel the structure’s substance in the unshakeable solidity and silence of the lobby. The marble stairs and wrought iron balustrade leading from the lobby up to the third floor are the only elements remaining from the 1913 structure.

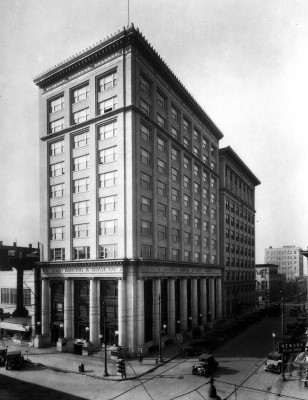

In 1928 Raleigh was growing substantially, and the Bank’s officers decided to add those eight floors, creating a Chicago-style office tower of steel-frame design, its engineering an affair vastly different from the original 3-story structure.

A portion of its south face was inset (think of the letter “E†with an abbreviated center element), yielding a light well which allows light to enter in case another tall building were erected immediately to the south.

While the early autumn sun shone on September 15, 1930, The Raleigh Banking and Trust Company failed (along with at least 100 other NC banks), exactly a year after the completion of the additional 8 floors. The building went into receivership, remaining in limbo until 1934 when the Massachusetts Life Insurance Company purchased it. A year later, MLIC began more renovations. The limestone columns guarding the first three stories were removed and replaced with simple brick piers.

I’ve seen many people wonder with pained expressions why those stately, classy columns were removed. My guess is this: a new age had begun in the US, and the building’s new owners chose to remove the more prominent reminders of both the failed bank and the Great Depression. Perhaps those columns, once symbols of stability and permanence, had become pretentious impostors. Whatever the case, the Raleigh Building shed its Neo-classical garb and took on the more informal, more dynamic Moderne style, the only tall building in Raleigh which made such a stylistic shift.

In the 1960s, my grandfather gradually let go of the reins and passed the management duties to my father, Bob Wollman. With a small but mighty staff who built many feet of walls, hung acres of vinyl wallcovering, replaced nearly every window, added the “missing†bathrooms (originally there was only one per floor) and dropped the ceilings, my dad ran the place in the classic Mom & Pop fashion. Our own night crew did all the cleaning and kept those brass elevator doors shining. Dad yelled at, cajoled, and made fast friends with the elevator mechanics who wrestled with the ups, downs and stickies of the automatic elevators installed in 1961. And with a pencil, his favorite office tool, he spent Saturdays keeping the payroll records on paper. Everyone loved the building. My father’s unceasing, insistent diligence and the building’s easy, relaxed atmosphere—strange bedfellows indeed—meant that tenants stuck around.

We built offices essentially to order. The head man on the job, Jesse Bean, was a master carpenter who overbuilt everything. His was a world of hammers, hand saws, and nails—pounds and pounds of nails. You could dance on the shelves he built. He joined pieces of wood with a precision few men ever achieve. Whatever he built was there to stay and could be demolished only with heroic efforts, yielding lots of little pieces of wood. Jesse was a large and strong man who worked his way, without compromise. My father gave Jesse the plans and then steered clear of him. The nail industry surely went into a tailspin when Jesse retired.

Southern accents and cigarette smoke ruled the air inside. Man, that was one smoky building. Ashtrays were mounted inside the elevators and even on the bathroom partitions. No one thought twice about it. In some offices, most notably a law office that specialized in saving the souls and licenses of people who liked to drink and drive, everything was yellow and sticky. Fortunately, the windows in the building are proper windows and can be opened for fresh air just like the windows in your house (but unlike the sealed, fixed glazing systems in modern office towers).

In 1990, on the heels of bad news from my father’s doctor, an order taller than the building itself came one spring morning when a pleasant woman from the City of Raleigh breezed into his office and summarily informed him that he had to bring the Raleigh Building up to the current high-rise code. That meant installing fire sprinklers, an alarm system, and perhaps a second stairwell—the last an impossible undertaking which would have meant the end of the structure as a viable business. As was his wont, he got to work immediately. With a lobbyist’s help, my dad’s efforts moved the NC State Legislature to pass a law protecting the few older high-rise buildings in North Carolina from what they saw as the capricious application of building codes. They called it the “Bob Wollman Law.â€

My favorite hangouts in the building were at the top, where I could contemplate the mysterious hollow in the center of the stairwell

and see all the way to the bottom as I wondered whether my spittle would land there; or see the whole of Raleigh from the rooftop with a mere 360- degree turn of my body.

And in the penthouse, high above it all, mine was the thrill of seeing and hearing the elevator machinery at work. The electro-mechanical controllers clicked and clacked as the elevator cars, tied to six steel cables moved by huge rotating drums, rose and fell within the shaft on sturdy rails.

When I played there on Saturdays with friends, we’d stage elevator drag races. Owing to this early exposure to elevators, I have no fear of them whatsoever. They still fascinate me, and I love to ride in them. The safety elevator, the brainchild of Elisha Graves Otis, is the sine qua non of high-rise buildings, making them far less “breath-taking” to scale.

Though the indestructible original elevator hoisting machines remain on duty (they don’t make them like they used to),

the building is now in the capable hands of Steve and Justin Lewis of The Raleigh Building, LLC. They’ve replaced the clickety-clack elevator controllers with silent, sophisticated Otis computer modules, refinished the heart-of-pine flooring buried beneath the carpeting on some floors, and brought the building up to the high-rise code. In the process, they’re keeping a significant part of Raleigh’s history flourishing. The love of the job, and the building, is in their blood.

Were he around today, my grandfather would undoubtedly find work for the painters. But both he and my father would be very pleased with the Lewises’ herculean efforts.

The Raleigh Building has been designated a Raleigh Historic Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and is this year celebrating the centenary of the original three stories.

Except as noted, all photos are the author’s.

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

07/15/2013

I’ve always been curious…what’s in the upper floors these days? Offices?

07/15/2013

You’re right, Nordy: offices, for as far back as I can remember—which is the early 60s, when no one could even so much as imagine living downtown. There’s a law firm on the 11th floor which has been there at least 25 years.

07/16/2013

Excellent article. I’ve always loved this building and was just in the CVS yesterday. I noticed a strange little elevator in the middle of the store. What was/is that?

I think the last elevator operator I ever remember seeing was in that building.

One minor quibble – In 1945, Jayne Mansfield (born in 1933) would have been a 12-year-old girl growing up in Texas. Maybe the note was dated 1955.

07/16/2013

Thanks, NCSU. You’re right about Jayne. Sure wish I had the letter from Mr. Heyman. It was a gas.

The little elevator in the store is a dumbwaiter that hauled store stock from the basement. Whether it’s used now I don’t know.

07/16/2013

Great stuff. I am persuaded by your theory about the columns too. It’s so easy for us these days to forget about things like that. We just see awesome old stuff and can’t figure out why anyone would ever get rid of it. Keep up the good work!

07/17/2013

This is a great piece…thank you! As far as elevator operators, I’ve never seen one in Raleigh (I’ve been here since 1993), but there was one in Durham at the Snow Building up until 2 or 3 years ago…seriously. There are two elevators side by side, one is not functioning…it’s the manually operated one, and now that they’ve stopped having an operator, it’s closed.

07/17/2013

Thanks, Brian. You might have to head to L.A. to find an elevator operator. A couple of years ago, the LA Times ran a story about a man who was a 35-year veteran of the job: http://articles.latimes.com/2011/oct/15/local/la-me-elevator-man-20111015.

But I’d be there might be one or two of them in Manhattan!

07/17/2013

Loved the article!

There are still elevator operators at the Grove Park Inn, probably because the elevator is so ancient and built inside stone walls!

07/17/2013

Russ-great story, and you are the only person on Earth to tell it so eloquently, with such authority.

The anecdote about the cigarette-hazed law office rang a long-forgotten bell in my brain. In the late 60’s, I took a ride downtown with my father and a neighbor. The guy had lost his license for DUI’s, and my father was giving him a ride to an attorney in the Raleigh Bldg. to see if he could help. The plan was for me to drive around the block as many times as it took for the two of them visit with the attorney upstairs…if there was no street parking.

As luck would have it, we found street parking, and I headed upstairs with the perp and his mouthpiece. The minute we got off the elevator…GAG!!!…a thick haze of smoke settled into my lungs. They left me sitting in the lobby when they headed into the attorney’s office. After about 15 minutes I could breathe no more. And my parents were both heavy smokers, I was used to it. The receptionist was chain smoking, everyone who emerged from an office had a butt going, my father and the neighbor lit up the minute they were in the elevator. It was too much.

I rushed, gasping, into the street, and went to wait in the car. The two men came back to the car in about an hour. The minute they were seated, they both lit up.

Double gag. I’ve never smoked a cigarette in my life.

07/17/2013

This is why I love living in DTR!!! So many old cool buildings with cool stories. Because the CVS on the street level is so ugly I have never looked up and really admired the beauty of this building, and I have never been inside. Thank you so much for the great story behind it!

07/17/2013

Thank you so much for the detailed history of this wonderful building. Your affection for it, and your love for your father and grandfather, shine through!

07/17/2013

Thank you for this wonderful story & great photos! So glad we still have this building.

07/17/2013

Thanks for the memories and history. I worked in the building for 2 years in the 90’s. On the eighth floor, with a huge window overlooking the Fayetteville Street mall. The floors and lower stairs were beautiful.

07/17/2013

“the perp and his mouthpiece” — I like it.

07/18/2013

Thank you for posting the story of this building. We’re next door and have been taking some second looks at the Raleigh Building. I never realized how much it was influenced by the Art Deco movement in the vertical addition, but as I look more carefully, there are plenty of indications. The cornice is misleading, the rest is Deco!

07/22/2013

This is a great article. A friend of mine used to work in that building and I always loved going up to his office to visit. I was always in awe of the windows that opened. He even took my on the roof like it was his place to escape the madness of work sometimes. It is pretty serene up there. I may have to go back and visit.

Thanks for this history lesson.

K

07/22/2013

There is a serenity, a freedom and an expansion on the rooftop. But on the penthouse roof, the wind could be fearsome. I can feel a weakness in my knees just thinking about it.

For too many years, my father refused to re-roof the building. Instead, he had me go into the crawl space to check the buckets placed to catch water whenever there was rain. Eventually, we replaced the roof. But the penthouse roof blew off in 1996 during hurricane Fran, and we lost an elevator from water entry. It took months to restore that elevator.

The current owners replaced the roof rather recently and got a top-notch job. I felt relieved!

07/23/2013

I also went up on the roof circa 1972 when a friend who was involved in some construction job had a key. He took me and a few others up there after dark one evening. The view was fascinating as I recall but of course none of the taller buildings existed yet at that time. I guess I can mention that it was Bobby Hocutt since his staute of limitations has now expired. :-) RIP Bobby.

07/23/2013

Bobby Hocutt. I checked his Classmate Profile on the W.G. Enloe website…an empty In Memoriam. This type of anecdote should be on his page, I will enter this link to his page, if that’s okay. As you said, jayare, his statute of limitations has expired.

No one should have an empty In Memoriam.

07/24/2013

Well done HWG.

07/24/2013

I wasn’t at all friends with him, but I knew him since Clarence Poe Elem. I relayed jayare’s anecdote to Bobby’s In Memory page, will be happy to include any other anecdotes to his page. You have to have a password to get into the Enloe site. Several classmates have emailed me thru the site, thanking me. Thanks, jayare.

07/25/2013

Somewhere, the Bobby Hocutt that we knew is saying “F*** You”. :-) He is a legend to those who remember.

He was best known locally for serving a jail term as an example, for selling a pack of rolling papers to an undercover cop in the ’70s when the paraphernalia law was first enacted. You can google it. It was very hard on him and afterwards he said to me “I almost lost my mind” over the situation.

Here’s a link to an article written by Peter Eichenberger, who is also no longer with us. I personally see a couple of inconsistencies in the article but it is basically sound.

http://www.indyweek.com/indyweek/raleigh-bad-boy-no-more/Content?oid=1198566

07/25/2013

Yes, I googled that article. It included some blog entries from people who knew him. I remember Bobby for being the only 4th grader who said “F••• You!” to our teacher, back before it was normal talk. Her face turned beet red, her jaw dropped to the floor. We couldn’t stop laughing. He, unfortunately, also taught the other 4th grade boys how to flip the finger. He got everyone in trouble.

I guess I can’t put those stories on his In Memory page. But it’s good to know he was a Raleigh legend.

07/25/2013

jayare, I put the link to that article on his Enloe In Memory page. I was waiting for a verification that that article was about the Bobby I was talking about. RIP, Bobby.

07/26/2013

Well, we really digressed from the original story here. :-)

Thanks for sharing the 4th grade story, which I can picture actually happening.

07/26/2013

RB won’t mind. Back to the subject.

07/26/2013

RB knew BH too. :-)

Bye.

07/26/2013

Yep, Bobby Hocutt and I were friends since 9th grade. After he jumped the Navy in 1970 he moved in with me at Page House in Boylan Heights. In 1972 he got the handyman job working for Mr. Wollman at the Raleigh Building. Bobby spent most of the summer of ’72 painting the fire escapes at Grosvenor Gardens. I don’t think they’ve been repainted since then — isn’t that right, Russ?

07/26/2013

They’ve been painted since then but…oh, well, that’s a topic for another spot ;-)

07/26/2013

So we’ve closed the circle. Let me know if there’s anything more you want to post on his Enloe ’69 In Memory page, I’ll be glad to do it;-)

RB, you were a Bad Boy? What a change from Enloe! I’m impressed!

07/26/2013

Thanks Karl for sharing your extensive knowledge of Raleigh history and architecture on this wonderful site. I appreciate the time and effort put forth here. Love ya.

J. R. (Jeanne)

07/26/2013

Ditto, RB.

07/31/2013

I hope someone will someday come and rebuild the columns. I know, I know. It wont happen

08/19/2013

This reminds me of my trip to the News and Observer here in Raleigh, it’s impressive the amount of old history that our buildings have. We often forget aobut it.

11/06/2013

Wonderful story!! Thanks to Russ for writing and to Karl for Goodnight Raleigh!

Though I never formally studied architecture, I find the whole subject very fascinating in terms of how it relates to the history of our city/state/country. And so many more stories are TBD (maybe the CVS facade will indeed be replaced with new columns?! who knows).

I also enjoyed reading the comments – sounds like there should be a whole other post just about these shenanigans!

PS – Is there a commercial architecture tour in Raleigh? I have been on several residential tours but would love to find out more about buildings like The Raleigh Building. If not, I would be happy to help organize one!

12/10/2013

I had no idea Raleigh had such a rich history. I’m new to Raleigh so it was really neat to find out all this great info about some it’s history. Thanks for the great article I really enjoyed reading it.

06/10/2014

Maybe Russ can confirm or deny this info about the RB.

If memory serves me correctly, the Sanborn maps (used by the insurance industry) showed the Raleigh Building as having timber structural members in its foundation – and maybe elsewhere – instead of steel or reinforced concrete. Of course, heavy timbers would have been quite normal for construction in 1913, especially if the building was to have no more than 5 or 6 floors.

Also, when I was a street urchin in the ’50s, the drugstore was Walgreen’s, not CVS. I know that Walgreen’s was there thru the ’40s and probably well into the ’60s, too. I can remember buying Wings cigarettes for 10 cents a pack there.

06/10/2014

Robert, I can’t recall seeing any timber in the original part of the building. I certainly remember Walgreen’s, especially its grill, where my father usually took breakfast. I usually had a fountain Coke during breakfast there, a choice I’ve long since abandoned.

06/10/2014

Thanks, Russ!

Those timbers would have been very large timbers on the order of 16×20 or larger and might have been covered with plaster. I know that heavy timber construction was sometimes rated better for fire insurance than was unprotected steel because it would take much longer to burn to a point of structural failure. Steel if unprotected will buckle relatively fast in a building fire.

08/09/2014

Here’s an interesting article regarding the Glenwood-Brooklyn are of Raleigh during the late 19th & early 20th century.

http://www.livingplaces.com/NC/Wake_County/Raleigh_City/Glenwood-Brooklyn_Historic_District.html

10/10/2014

Thoroughly enjoyed reading the blog post and comments by you all. Thanks!

12/01/2023

It’s fantastic that you are getting thoughts from this post as well as from our dialogue made at this place.