A Forgotten Treasure: The Raleigh Water Garden

I started out with only a Facebook status update and the vague directions “across from the Carmax on Glenwood” to go on. An hour and a half later, I found the Water Garden.

Walking along Glenwood Avenue after it leaves downtown Raleigh, one feels beyond doubt that this is not a place intended for human traffic. Furniture warehouses and car lots sit in misanthropic isolation off of a busy road with no sidewalk. You’re not supposed to walk around here, and if you do, you feel small and lost in a blinding, concrete commercial desert. On foot, you realize how far apart everything is, how much space there is that possibly no one has walked in years.

When I finally found the entrance to the Water Garden, I was surprised I had missed it. It looks like a sign for some vintage funland. Walking down the gravel path from the treeless light on the road, the light gains compassion, becomes photosynthetic, happily leafy. It was surreal, walking off of the hell of Glenwood into a place with such spiritual resonance. I had no idea what any of it meant. It was only after poking around for a while that I discovered:

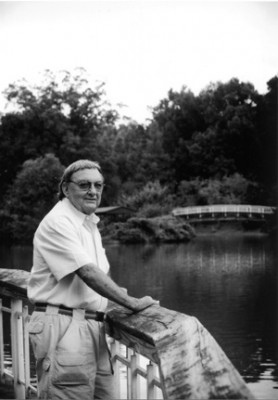

- It was the home base of Richard Bell for over 50 years

- Richard Bell is one of Raleigh’s iconic landscape architects

I was able to meet with Kim Weiss, Bell’s biographer and close personal friend, and later with Bell himself, and this is what I learned.

Richard Bell is perhaps Raleigh’s most beloved landscape architect, although fewer and fewer people know who he is. Bell created landmarks like the Meredith Ampitheater, Pullen Park, and NCSU’s Brickyard, and the beautiful gardens surrounding the Legislative Building. In a real sense, Bell has shaped the ethos of Raleigh in a way all of its inhabitants experience. Bell, or Dick as he’s known to friends, left Manteo in the late 40’s to come to what was about to become Henry Kamphoefner‘s newly established School of Design. Kamphoefner’s vision was to not simply create a talented body of graduates versed in philosophy and the practice of design, but for those graduates to set up shop in North Carolina. Essentially, Kamphoefner dreamed of creating an infrastructure of modern design in North Carolina, not just a school of design in Raleigh. “We were orchestrated to work in North Carolina,” Bell told me. “Eighty-five percent of our graduates went on to work in North Carolina.” Bell told me that Kamphoefner insisted that his faculty not only lecture, but also practice their disciplines, and had distinguished individuals such as Frank Lloyd Wright come and talk to the students. Bell chuckled as he told me that Wright refused to lecture in the Design buildings because he thought they were so ugly. Bell met Wright under a tree near Holladay Hall. “It was an open ended school,” Bell reflected. “Kamphoefner had a master plan for development.”

Kamphoefner’s intense program of training worked, and in 1951, Bell won the Prix de Rome at the age of twenty. “It was- How would you say it?- totally weird,” remarked Bell. He was the youngest individual to ever receive the prize, and in a bold move, asked the committee to delay his acceptance of the prize until he was twenty-one. Surprisingly, they agreed, in part because they appreciated his desire to apprentice in a working landscape architecture office before going to Europe to study. He traveled to Italy and toured thirty countries in Europe, and remarkably for someone raised in the pre-civil rights South, often travelled on a Lambretta scooter with a black sculptor. He cited this experience as a major influence on all of his later work: “It gave me a broader perspective, and that was incredibly valuable.” He came home inspired, ready to start designing in North Carolina.

The Water Garden began when Dick stopped along a then-rural stretch of Highway 70, helped his new bride Mary Jo out of the car, and told her, “If we ever have a place, I want it to be like this.” He told me about showing the site to her that day: “It was so beautiful. The sky reflected in the water. It was way out in the boonies at that time… but there were wetlands, pines- It was a mini-environment of bog and plants.”

There was already a foundation for a building on the property, and with the help of architect John Evans of Florida, the Bells designed and built their modern home over it. The first building became known as the “Chicken Coop”. It was rough going. The Bells did much of the work themselves, and by that time the couple had two young children. “It was rough,” said Bell. “We had two kids, $7000, a plywood floor, and newspapers over the windows for insulation.” But gradually the buildings were completed. It took about 14 years to build the Water Garden, from their first house there to the ultimate office park, gallery, residence and gardens that spread over 11 acres. Finally, in 1963, the Bells held the first art show at their Garden Gallery. Even more than just being a breathtaking piece of modernist design, the Water Garden was crucial for Bells’ career and mission on two levels.

First, Bell used the Water Garden as a laboratory, constantly trying out new ideas and combinations of plants. “I didn’t feel like my clients ought to be guinea pigs,” Bell told me. Bell had inherited a love of plants from his father, Albert Bell, who helped design and build the Lost Colony Amphitheater. Bell grew up in his father’s and grandfather’s nurseries on Roanoke Island, and his green thumb combined with a creative mind produced some innovative ideas for gardening. It was Bell’s idea to create berms around pine trees up to eight feet high- previously, gardeners had assumed that a berm that high would kill pines. Nurseries would send Bell plants to experiment with, and Bell was the first person to take many local plants out of the forest and use them in residential design.

Secondly, and perhaps more crucially, Water Garden was critical in establishing the profession of landscape architecture in Raleigh. Bell built the Water Garden, not only as his home, but as a place that he could point to and say “There. That is landscape architecture.” In a real sense, the construction of the Water Garden was the foundation of Landscape Architecture in North Carolina as a whole. It was a showpiece that opened the door for Bell’s other projects, projects which have helped define Raleigh and the idea of landscape architecture.

It was so interesting to come as an unrecognized pracitioner of an unrecognized profession and say ‘This is what we should do for our city.’ It all came about as a kind of mystical relationship between me and my clients.

Bell’s goal in all of his projects was not simply to create beauty, but to establish landmarks to show what Landscape Architecture could do. ‘Water Garden’ was the first landmark.

Bell’s vision for the Water Garden was that it would be a mixed-use building, in which work, play, and the fabric of living were integrated through the beauty of its design. He saw it as a place not only for living, but in which living and art and design were side by side. The Coop housed a gallery, and the first art opening was held there in 1963. “Mary Jo was in charge of the gallery,” he told me. “We had a sculptor and a painter for the first exhibit.” The Water Garden soon became the cultural center of Raleigh. I work with an older lady who has lived in Raleigh for over fifty years, and she told me that she used to go out to the Water Garden on occasion. Kim Weiss told me how Raleigh’s arts scene in the 60’s and 70’s had its epicenter in Water Garden: “People would tramp out there in the rain. It didn’t matter- they just wore boots.”

As the decades passed, Bell remained prolific in his work but the arts scene moved downtown and development along Glenwood Avenue/Highway 70 West began  to encroach on his and his wife’s oasis. Water Garden was no longer the haven it had been before Raleigh began its spastic sprawl: Cookie-cutter housing developments were being slapped together around the property, and at night, you could see the neon signs of a car dealership through the trees.

Bell knew it was time to leave. He assumed that the property would be passed to his children. Unfortunately, this didn’t happen. Although his daughter and son-in-law were able to take over the design firm, taking over the care of the 11-acre property was simply too much.

“It was rough leaving,” Bell told me, staring into his cup of coffee. “We hadn’t created the proper background for our family to take over. It wasn’t a happy time.” Bell had thought that perhaps the city would buy the property, but Water Garden wasn’t old enough to attain historic status, and Bell ended up selling the property and buildings to developers. “On one hand, he was glad to have [the hassle of taking care of the property] off of his back,” Kim told me. “On the other hand, he spent his life there. It was- and is- a huge loss.”

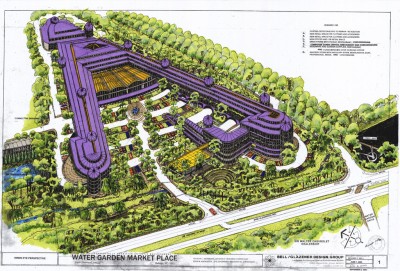

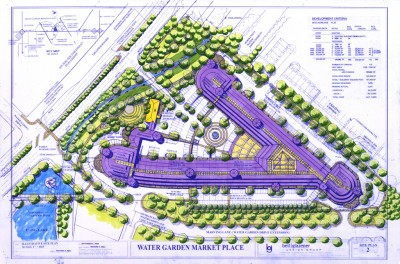

At the moment, no one is sure what will happen to Water Garden. Bell worked tirelessly, and on his own dime, to design beautiful building plans that would allow the developers to preserve the original buildings while incorporating them into larger development schemes, such as a shopping center and a senior care facility, to name a few.

“The senior living one was the best one,” said Bell. “I tried to present a plan of adaptive reuse.” The developers didn’t even thank him for his efforts.

Since the property was sold and vacated in 2007, the state of the buildings has grown steadily worse. The place looks like it’s been sacked by Vikings. Scrappers have gutted the walls, most of the windows have been shattered, and traces of paintball wars splatter the walls.

Since I began work on this article, gates have been put up to discourage local vandals from inflicting further damage, but much of the mutilation was a result of the sherriff’s office using the property for training. After a group of high-school students vandalized the property last year, Habitat for Humanity was allowed to salvage what they could.

No one is sure now what will happen to the property, but whether or not the buildings stand, Water Garden will remain a beautiful and central part of Raleigh’s history. “Dick always envisioned Water Garden as a place where people could live, work, play, and interact,” said Kim. “And for a while, it was. It does make me sad, but I know Dick has many monuments. They will live on.” On all of the occasions I talked with her, she didn’t seem to be at a point of resignation, but then neither am I. And perhaps for those who have experienced Water Garden, in any capacity, that resignation will be a long time coming. “OK, Water Garden will disappear. But all the other landmarks Dick designed… Those are still there.”

Many thanks to Kim Weiss for all of her help. Dick Bell’s first book “The Bridge Builders”, edited by Kim, comes out soon.

Unless otherwise noted, all images credit John Morris

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

10/14/2010

I agree that there are many sides to this issue. I think the main thing that has disappointed me is the language used by some of our neighbors. While I totally understand the concern about over-development and the removal of our green spaces and privacy, I think the “fight” and the conflict should be about those things and not about terms like “riff raff,” etc. Such languages devalues people and is not productive toward finding a solution to this situation. It is my hope that if the understandable land use issues are really the concern that the same “fight” would be taking place if a business or a “high end” development went there. Perhaps I have been quick to judge, but the tone of some of the comments has been offensive. I agree that the irresponsible development of every square inch of Raleigh is an environmental and “quality of life” concern. Some people may be concerned mostly with this side of the issue, but others are focused on the nature of the potential residents in a way that seems very judgemental. I hope that a solution involving a more appropriate entrance, bettter use of the roads (this is a valid concern regardless of the type of development being built), etc. will be reached and will allow us all to live in this great community. Thank you for being respectful and clear in your response to my comment. That is the kind of discourse that will bring about a solution.

10/14/2010

Thanks ks. I agree that many comments left, especially the ones including phrases like “riff-raff”, have been offensive. I understand concerns residents may have about property values and other issues that have been addressed as being legitimate concerns, but the attitude of discrimination against poverty is exactly the opposite of what Dick Bell tried to achieve in his career.

10/15/2010

Tom/JR/KS and whoever else who thinks we can stop DHIC, it isn’t happening. What we CAN do and NEED to do is work with them and try our best to get them to at least understand our concerns and hopefully address them. I have a realtor friend who is very knowledgeable about this stuff and has actually contacted the city and DOT directly. The Marvino lane ‘extension’ has been planned since BEFORE Long Lake Subdivision was put in. If you look at the physical road it is cut and angled to continue through to Glenwood. She said the DOT has to put it in and is even apparently paying for it. The other side (the towns) apparently is not an entrance, we were told it will be chained off and used only for fire emergency purposes. We should clarify that. Either way, we can’t stop DHIC since they are funded by the city, the DOT, and the federal government. What we can do is try and force them to leave large tree buffers and preserve as much of our ‘back yards’ as possible.

One thing everyone seems to forget is that *we* don’t own the property. We never have, nor has Pulte. It went straight from Dick Bell to these current owners, to DHIC. So the views and the natural grounds there that we take for granted have never been ‘ours’, we’ve been borrowing them. So again, we need to try and get DHIC to leave as much buffer as we can!

Also, Rob- your idea of buying the property from the current owner is an interesting one, but also a no-go. They’ve been contacted multiple times by outside parties according to my realtor friend and apparently they want DHIC to get it because they believe they are doing what is best to preserve the land compared to other options.

Sad we scared the ‘current owner’ out of this forum because it sounds as if he or they were decent people and probably could have given us a lot of information. They have also rescinded any offers for people to come see the property in light of the issues being raised and took their email off of here (it was on here originally, I know I saw it).

Moral of the story, we can’t stop what is going to come, what we need to do is COME TOGETHER and talk with DHIC and make sure they understand our point of view!!!

10/18/2010

As the moderator of the Long Lake Message Board, I have reached out to the owners of this page to say exactly what many of you have said previously, that as a community of 847 families we all have different opinions, and those that were shared are not necessarily the ones of the HOA or the community at large. As I have stated in our group, I request that our community stop using this this page as a bully pulpit for personal feelings on the development, and please come back to the community page to carry on the discussion there. As I have stated time and again peoples rights to their opinions are guaranteed by me, and I will not tolerate defaming attacks by neighbors, if anyone wishes to post anonymously they know they can e-mail me and I will post in my name, but please can we stop airing our dirty laundry in a public forum? Danielle and the other owners and writers of this page, thank you for allowing people to use your site, and again I apoligize for some of our neighbors offensive comments

Rob Sullivan

On Behalf of the Long Lake HOA

11/02/2010

Hi there,

I’m with a web design/development book club, and we are reading a book this month about “wabi-sabi”, the beauty of impermanence. We would like to take a field trip to Water Garden to take photos and discuss the beauty in the destruction, so to speak, before it’s developed. How can I get in touch with the Current Owner to arrange this? We’d like to be above board and sign whatever waivers are required for this exploratory trip. Please help us make it happen!

Thank you!

12/08/2010

Offensive Comments?? What a mess they made of the place!! Shame on you Black Mountain Development!! I hope you don’t treat your home and kids they way this place was trashed. Paintball! Give me a break!! Grow up and buy things that you can make useful instead of trying to find some kind of profit off everything! You probably lost money in this deal anyway. Said you bought it for 1.6 mill eh? Such a price to pay for paintballing and now what you just throw it away for it not being “up to code”?? If you had 1.6 mill to spend why didn’t YOU make it up to code or make sure it was usable before buying it and messing it up!! I would be mad if I were Bell. I bet the money from this will be used for another play yard for them.

12/14/2010

ddmeadow5 – sounds like you have been doing a little trespassing lately, eh?

Well now that you got your rant out, perhaps you can take some time to understand how the ‘real world’ works. If you read the comments above before flame-posting you would see they DID TRY to do something and couldn’t get it together, so they sold it to what they believed was a good cause. Despite what you may think, the world does not revolve around you and your hopes for keeping everything pretty. IN addition, Bell made good money on the sale and from the people the owners have on the hook buying the property now, so likely are they going to make good money on it.

Take your hateful statements somewhere else. This story is about good, and you are clearly not that.

01/07/2011

I’ve spent the better part of an hour reading this thread. Mistakes have been made all around and it’s a shame that first, the city didn’t step in earlier and develop this into a park, second that Bells estate was not smarter in terming the deal of a sale, third that the current owners have not seen the value of the history and art but instead leased it for destructive uses without regard for preservation, fourth that the local community didn’t fight for the property in the proper forums before it reached this point.

What’s more disheartening is the blatant classist attitude held by some of the locals who devalue the humanity of addicts, the poor, and the old over their property values. They are people too and most of them are good people who have found their way into bad situations. I feel bad for anyone who opposes section 8 housing then finds themselves homeless.

I personally am not a fan of “developers” because, though they often claim big when pitching their ideas to zoning and planning boards for permits, follow through is usually lacking and the finished product never approaches the grandiosity of the ideas that got them their permits…product doesn’t match the sales pitch. Bottom line is that the developers numbers run on profit margins not quality of product or artistic and historic integrity.

It’s a shame to see this property go and maybe the developers will have the good sense to think long term and hire an architect to build the water garden back to its former glory while integrating it into the design plans for the property. Intangible and community value lasts longer than $$ value.

02/06/2011

That was a very liberal way of putting it. The residents had no chance to stop anything by the time the N&O reported it the city put on their duntz caps. Politician after politician laid down on it, deferring their comments to fair housing and their assistants since they did not do their homework. Defending it with the fair housing laws was the best way for a mute response. (fair housing laws have become so insane). How come I can’t buy a house I can’t afford, but someone else can live in a brand new government provided home that my tax payers dollars supports……….. I believe in charity, and helping people in need. However this is a new system the government has created to allow for people to live in government funded lifestyles throughout their lifetime. We wonder why school teachers are getting laid off, why there is no money in the cities budget to do things for others. Then we sit back and watch them donate this to less fortunate as we call it, of which I am sure will be good people with your average bag of bad apples. However, a high percentage will be that of who will live their life through this government system. Where does it end…. America is a funny place, have a job and you may not get bye in life but paycheck to paycheck. Don’t have a job, and those of us living paycheck to paycheck will see to it you live as comfortable as I do. Its strange how liberal and small hints of socialism have creeped into our lifestyles or even our backyards.

02/09/2011

Thanks for the article it is like someone dying with cancer a long slow death. So much of the past has been gobbled up in asphalt and cement…no where to breath or have a quite moment.

02/17/2011

The Water Garden was demolished this week. It was really beautiful once upon a time. So sad to see it go.

02/28/2011

They are still tearing it dow now, come sit in my house and listen to it. Apparently it takes 3 weeks to tear it down, even though they start at 6am. Oh I can’t wait till the construction kicks in and I am up every ay at 6am listening to this!!

03/19/2011

RIP WG

3/19/11 we are currently at water garden and it is no more.

03/19/2011

Thanks for the update Jennifer. The Water Garden will be long mourned by many. If you took some pics today, send them to us and we will post.

03/28/2011

I remember seeing this wonderful place for years, as far back as when it was a two lane road near the angus barn to get to RDU. I never knew there was so much more to it than what could be see from the street. Sad to see it in such ruin. It always seemed like a little oasis around the encroaching development. Let it live forever in old pictures and memories. Maybe at least the sign can be preserved.

04/13/2011

Mr. Sumner was the owner of that disaster…nobody was trespassing he let people paintball there and THEY told the story. ddmeadow5 was right and I don’t see where he was being “hateful”. The owner made money off paintballing too charging people to rent the property to destroy whatever they could so if they signed waivers to enter they were not trespassing. That’s why he has an aston martin and a 1.9 million dollar house. So all the money he has he couldn’t have done anything but paintball with the property??? I feel so bad for what was once a nice place to be treated in such a manner all of you supporting the owner should be a ashamed of yourselves.

RIP Water Garden.

04/13/2011

To “Jeff G” – Accusing someone of trespassing when there are pictures of the damage on this page is unbelievable. I just read all of these posts and it seems to me the owners have to defend themselves quite a bit. I guess you are probably one of them (since there is accusing going around)?? I did see the property before they owned it and yes, I saw it today and that is what prompted my searching the internet for details. I am shocked to learn what has become of this place and I hope that these developers really look into what they are buying BEFORE they buy. Even if Mr. Bell made money off the deal, it seems that all his hard work was flushed away and now will be forgotten and left only as a memory for those who were lucky enough to have experienced the property for what it was.

Water Garden will be missed. :(

04/13/2011

There is something that is called “FREEDOM OF SPEECH” – And I am soooo glad I came across this post!!!

Section 8 housing is what the ownwer of black mountain development’s child grew up in. Yes, that’s right!! Maybe it is his way of “giving back”….sad to know he is running around buying million dollar properties and riding around in nice cars while his son is forgotten in Maryland. Karma baby!! So much for free rides and maybe some of his profit can go back to Maryland for supporting his son all those years. And we wonder why the goverment is in such debt…dead beat dads running around hiding assets so the goverment can pay for their forgotten children. Give me a break!

04/13/2011

How funny – Doesn’t he own Redtail-Gatson too! They donated 50k to local charities….maybe they forgot Maryland in all that….

“Redtail Gaston LLC, developer of Eaton’s Crossing, a new, upscale community on Lake Gaston in Warren County, donated more than $50,000 to North Carolina charities during its first year of operation. The majority of these funds were given to charitable organizations in Warren County”

04/14/2011

If you suspect or know of an individual or company that is not complying with the tax laws, you may report this activity by completing Form 3949-A. You may fill out Form 3949-A online, print it and mail it to:

Internal Revenue Service

Fresno, CA 93888

04/20/2011

Matt sumner is listed as the registered agent for Black mountain development and redtail-gaston. He has had several llc’s opened and closed in the past few years. I wonder what kind of tax dollars are being hidden in all that mess. I wonder what all of the managing partners think of all this riff raff. The man needs to step up and take care of business like it should be. As for the child in maryland..if that is true, he should take responsibility and see his child and provide in the manner that he can support. Anyone who has the money to drive around in luxury cars should be able to drive to see his kid – period! In the end, it won’t be the mother’s or child’s judgement that he will face….hope he keeps that thought close to heart!

10/22/2011

I was browsing the internet when I came across this webpage “The forgotten treasures of Raleigh”. I been living in the triangle for over 50 years and I never knew this place existed in Raleigh and wish I had the opportunity to visit the place when it was open. I love art, sculptures, water gardens, water falls and over the years I have created the same kind of rolling landscapes, flowering plants,walking trails of my own design as Mr. Bell has done, but the architecture is not even close to the beautiful flow in construction and design that he has achieved at Water Gardens.

I am inspired with this article posted by Danielle Carr . I love reading this story and reading the entire thread to the end. I loved looking at all the posted pictures from Mr.Dick Bell, but near the end it was very sad and now the place is gone in three days, when it took 14 years to construct. This has been a real learning experience and I won’t forget it.

Thank-you for having this on the bit of history for all to see

God bless.

~~Daniel S.~~

10/22/2011

I forgot to add myself to your emails,

Daniel from Pittsboro NC

11/23/2011

I have been following this closely as I live in in Long Lake and I have currently lost EVERY TREE behind my house. DHIC says they want to be green and a good neighbor, I can tell you they are doing anything but that. Every tree has been removed from behind Long Lake and going to replace them with new ones, I am sure they will be short trees, that provide no privacy for the residents in Long Lake. Thanks for being green. Also they claim to be good neighbors, they work 7 days a week, starting at 7am Monday through Saturday and 8am on Sunday. As a resident , I understand this will happen, however the DHIC is not honest, they claimed they where building senior housing, which we all knew was a lie because they refused to show us a plan for it, guess what, they aren’t building one. The DHIC has been around for years but also claims to have no statistics on crime and property values, when in truth they don’t want to show you. The management company of the apartments doesn’t let in violent criminals, only ones with nonviolent crimes (like buglary-as they stated in one of their meetings), which is very comforting to the long lake residents. They are selfish and don’t want to work with Long Lake, they have not shown us anything to make us believe them.

This could have gone over much better if the DHIC would just be honest and disclose the information, we all know what it means but to deny it or pretend it doesn’t exist if just plain foolish.

I hope I am wrong and this will turn out to be nice, with trees and very little issues but the records so far don’t point that way.

11/29/2011

I’m with WRAL-TV, and I’m interested in talking with Long Lake residents about this project. If you’re willing to talk on-camera, please call me at 919-821-8503 or e-mail me at bshrader-at-wral.com. Thanks!

12/28/2011

Drove down 70 today and noticed that 90% of the trees are gone as well as all of the structures. All that is left is a giant pile of dirt.

12/29/2011

I moved to this area of Raleigh in ’69 and have seen the drastic change of urban sprawl. Water Garden for all intents and purpose was spoiled long ago. For those people in the Long Lake community of 850 residents, I HAVE NO SYMPATHY.

02/02/2012

Great pictures. I remember as a girl going to the water garden where my father (Ralph Graham) worked. Ralph was a partner of Dick Bell and Dan Sear in the 70’s. It was a beautiful place that was very fun to explore as a child. I am proud of the work my father did which included design work on many of the projects listed above. I will always try and remember it as it was back in its prime.

03/17/2012

http://www.dhic.org/news/2010/watergarden_pr_2010.pdf

05/28/2015

I am the youngest daughter of Richard Bell. I grew up in the Water gardens.I remember the art openings and grand parties held there. I grew up with artists, art and architects all creative people. I left for a few years after marrying and 4 children but came back for its final years. I am so glad my kids got to experience Water Gardens and even had some of their own parties there. I will always miss what I called “Little Camalot”. It was a magnificent place. I also know it held my father’s heart.Thank you to everyone’s heartfelt comments. RALEIGH REALLY MESSED UP BY LETTING IT GO.

05/11/2017

Would have been a beautiful park!

02/28/2018

I had the honour of working at the Water Garden in the 80’s in grounds maintenance. My friend Bob Bainbridge worked there and got me the job on my return from working and living the UK.

It was a delight. Full of so many treasures and interesting design concepts. The parties were GREAT! I believe the son-in-law and daughter were called Denis and Sharon. They were great friends with a Ms Leslie who worked for a company designing equipment for the disabled. I feel madly in love with her. We had great times, though short, as destiny took me back to England where I have remained. I would love to know what has become of her. She was one of the great lives of my life???? I look back with great fondness to those heddy days when I was 30, full of hope and adventure!

Sincerely,

Randal Anderson

Devon, England and Kerala, INDIA

10/10/2018

Amazing add to the assortment. bring 3mw6h http://3mw6h.gq/ with anything ! I fell in enjoy with it! You wont regret this purchase. Itll be your every day fav!

02/26/2020

Tremendous things here. I am very satisfied to look your post.

Thank you a lot and I’m looking forward to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

05/15/2020

I got this site from my friend who told me on the topic of this web page and at

the moment this time I am browsing this site and reading

very informative content at this place.

11/19/2020

I have many fond memories of the Water Garden. My late father was a sculptor and painter and displayed many of his works at the Garden Gallery. What a delightful, inspirational place.