The Fabius Briggs House: A Crumbling Raleigh Relic [Updated]

For more than a century rain has been mulling over a way to make a home inside the once regal house on the corner of Ashe Avenue and Hillsborough Street. The house, often referred to as the “Green House” or “The Jackpot House”, drops slate roof tiles as if it were inviting its wet foe inside for an extended stay. The perimeter of the house is littered with malt liquor bottles, window glass, and broken slate.

A story accompanies every house that man inhabits. Much like children, we give these organized piles of lumber and stone an identity of their own when they become the structural shadows of their past residents. The Jackpot House wears its history in plain view. Its weathered green asbestos siding, peeling paint, gray wood, and cinder block appendage tell a vague story of neglect and abuse.

During the late 1800s and crossing over into the first few years of the 1900s, residential development crept onto Hillsborough Street, and the tract along Ashe Avenue between the railroad tracks and Hillsborough Street was in the process of being sectioned off for development. It was during this time the Jackpot House was constructed.

Wake County tax records indicate a build date of 1915. However, city directories and deed research suggest an earlier date of around 1902. The Queen Anne-style architectural details such as the hipped roof with lower cross gables and the gabled dormers also suggest this earlier build date. Porches are very significant in dating a residential structure, but sadly only a small portion of the original porch still exists. It is very likely that the original building had an asymmetrical porch that ran the width of the house and along half of the left side. The portion that exists today is a good indicator of how the original appeared, but it is still difficult to imagine what this house looked like with a lawn and a front porch.

If the house had any dignity remaining before the Jackpot was built, it was lost when the porch was removed. As journalist Michael Dolan once said, “a house without a porch is like a man without eyebrows”. Sifting through its catalog of structural scars reveals a more accurate picture of how this structure came into its own identity, and leads to more questions that beg deeper investigation and further speculation.

It is believed that the house was built for the family of Fabius Briggs, a son of Thomas H. Briggs, the founder of Briggs Hardware. In 1874, the Briggs Hardware building on Fayetteville Street was Raleigh’s tallest building and remained so for three decades. The Briggs family has deep seated roots in Raleigh and the family business continues to operate today. The Fabius Briggs family lived at 1301 Hillsborough Street until around 1927. By 1929, the Great Depression brooded over the city, and in 1932 the Raleigh Building and Loan Association acquired the house through foreclosure. It likely spent a time unoccupied, and was eventually rented to a Raleigh lawyer, and then to the Sigma Nu fraternity for ten years.

By 1944, the once palatial residence had been humbled and abused by its tenants. It had lost its innocence, status, and shine. It was around this time that a Greek family by the name of Kledaras bought the Briggs house, which they would own for the next 60 years. In 1949 an architect unwittingly drafted the fate of the old house alongside plans for three storefronts: a dry-cleaners, The Brite Spot Restaurant, and a contractor and building estimator.

Present day, store fronts

One might wonder why someone would destroy any outward aesthetic appeal of a turn of the century Queen Anne house by attaching an ugly cinder block building. Simply put, in the mid 1950s this style of architecture was out-dated and all too common. In the eyes of a 1950s Raleigh resident, 1301 Hillsborough Street was a throwback to a time that was becoming increasingly hard to identify with. In recent years, the Garland Jones building in downtown Raleigh gained attention for its modernist exterior and was considered ugly and outdated by many Raleigh residents. The revolving door of architectural trends had come full circle. The Raleigh residents who designed and built Garland Jones were also razing and turning their collective noses up at gaudy, ornate turn of the century architecture. We are simply mirroring the actions of our ancestors with a new aesthetic ideology.

By the 1960s, the three storefronts and a rooming house occupying the Briggs House itself had been open for more than a decade. The 1970s proved to be a rough time for the house and its appendage. The Brite Spot restaurant became an aptly named strip club bearing the same name. The house, virtually abandoned at this time, naturally became a place for patrons of the strip club to get “privacy”.  The house had become a den of iniquity, and would remain so for some years to come. When the city cracked down on strip clubs in the late 1970s The Brite Spot closed. The cinderblock building was then home to a long list of bars and other establishments, while rooms in the house were rented out — or left abandoned.

Fireplace, main floor

A beautiful oak staircase runs along the left wall and turns up at a right angle to the second floor. Walking up, dark wood surrounds you. Waist-high rail and stile paneling runs the length of the wall opposite the banister, worn smooth by thousands of hands. The steps have become concave, and the walls seem to ache with age.

The future looks bleak for the Briggs House. Recently condemned by the city of Raleigh, its days are numbered — unless it is either brought up to code, or moved. Preservation North Carolina (PNC) is working to save it; however it seems the only way to preserve the house is to move it. This option would require a tremendous amount of effort and money. The gleaming question is whether it is worth all the trouble. History buffs and architecture geeks would certainly chime in with a resounding “yes”, but sadly the majority of people would remain apathetic to its destruction.

Whatever the future holds for this old structure, one can confidently attest to its long life and steadfast nature. Personally, I take comfort in knowing that I’ll be here in 30 years, telling a new generation of Raleigh residents — “There once was a wonderful old house that sat right there” — the very words that I find so fascinating today.

[Post updated April 30, 2011]

Definitive plans for the Briggs house have been increasingly hard to come by. What we do know is that the house is still on-site and is still racking up reprieves to its ultimate destruction or, optimistically speaking, its relocation. A fourth 90-day extension was granted by City Council earlier this month, and it will probably be the last. Following the demise of the Jackpot last Fall, the structure has fallen victim to increasing vandalism, specifically to the interior. The exterior is gradually crumbling as well, and nearly all the windows have fallen out. Hopefully some sort of resolution will come soon, so the house can either be moved or carefully dismantled to save its valuable interior artifacts.

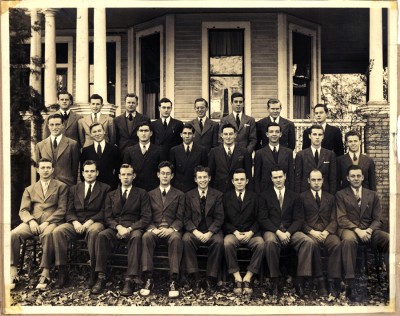

Recently, Goodnight Raleigh reader W.E Carter sent us a revealing photograph from 1941 picturing the brothers of Sigma Nu fraternity. This photo is an amazing documentation of the Briggs House, to say the least. The photograph shows what we’ve all been hoping to see — the long-lost front porch. The paired double-columns and the buff-colored brick plinths are typical of the Queen Anne-Neo-Classical-Colonial Revival transition style house so popular in Raleigh at the turn of the 20th century. The porch details should be familiar to discerning eyes, as part of the original wrap-around porch still remains on the left side of the house.

Goodnight Raleigh will keep our readers posted on any new information we may learn about the ultimate fate of the Fabius Briggs House.

Sigma Nu brothers pose in front of the Fabius Briggs House in 1941. Mr. Carter’s father, Wilton E. Carter, Sr., is the young man seen third from the left, top row.

Below are some parting shots I got of the interior a few days ago.

Detail of the incredibly beautiful stair hall paneling.

Doors to nowhere?

Sign up for the Newsletter

Sign up for the Newsletter

02/24/2011

WE Carter, I am VERY interested in this.

We’ve been looking for a picture of the front porch for quite a while now. If you’d be willing to share it, I’d be very grateful!

IFGDunn@gmail.com

02/25/2011

Send me your email to wecarterjr@gmail.com and I will send you the two photos from 1941 and 42.Photos just show portion of front porch as photo is a group picture of the Sigma Nu fraternity.

02/25/2011

Ian, please post any additional photos of the front you find. Would love to see how it looked. With those fabulous stairs, would love to see the building restored. Hope Preservation NC can help.

04/26/2011

Any updates on the current status? We’re well past October and it’s still standing (or at least it was the last time I passed by, a couple of weeks ago) but I’ve not heard any news recently. Seems the impending redevelopment of the blocks adjacent to the Bell Tower and to University Towers have occupied most of the news coming out of that area lately.

Also, I too would love to see those pictures of what the front porch looked like.

04/30/2011

Chris M. and Nancy,

Post has been updated. We will continue to update as new developments unfold. Thanks for reading!

07/05/2011

I was wondering if the Briggs house is still standing and if it is still available. I e-mailed the Preservation Society a couple of months ago about the Briggs house, but never heard back from them.

I know that it would take a good deal of time,and yes, money too, but if at all possible, I think that this would make a lovely home to raise my grandchildren in.

07/07/2011

The Briggs house is still there, but I don’t know what’s going on with it. It is now all boarded up with plywood including the night club in front.

07/10/2011

Local painter Kenneth Eugene Peters recently did a painting of this house that is great, check it out http://kennetheugenepeters.com/Pentimento_Fabius_Briggs_House_Painting.html

07/10/2011

Ok, since it is still standing, I would take it to mean that it is still available. What is the best way to get in touch with the people that are actually selling the house? I know that it is to be moved to another site, but I neither mind or care. I want to buy it if I can.

07/11/2011

Contact Jason Queen at Preservation NC. He’s been trying to work with the owners.

07/11/2011

Unfortunately, we are coming up on the final deadline this month.

07/11/2011

I just sent Preservation NC an e-mail requesting the necessary information for the purchase of Briggs House if it is still possible.

While there are several factors to be looked at, especially the timeline and what kind of work will be necessary, if this can be done it will be well worth it.

07/12/2011

G. Olsson – Please send me your request directly. jqueen@presnc.org

07/24/2011

Did any one notice the transparent hand on the rail of the staircase besides me.

11/15/2011

Did anyone notice the fresh bouquet of flowers seen through the banister under the hand. Demolition has started of the Bolton buildings across the street and I believe the Jackpot and Green House will be gone by 11-30-2011.

12/01/2011

Those flowers are the same ones on the red-tiled mantel in the “Main floor fireplace” photo above. I presume they are silk, but you never know…

The Bolton and Stoudt buildings are completely gone at this point. (12/1) Removal of the Asbestos siding, windows, etc. has commenced on the Briggs house but as of this afternoon the old girl was still standing. That will probably not be the case very, very soon though.

12/05/2011

Gone today. RIP Briggs House.

07/18/2013

Dear Ian: What a lovely and respectful tribute to this wonderful old dowager. Like you, we love the elegant old homes whose zenith may have been passed, but whose station in life is realized. I hope and pray this grand home will be preserved — by moving her if need be. God bless you for your gentle, loving words. She deserves them. (I, too, wondered about the “hand” on the staircase banister. Did you see it as well?) Thanks again.